Chief Savage Man

Active member

Part Ten: Don’t Let The Giant Out Of Bed (North America: April – August 1939)

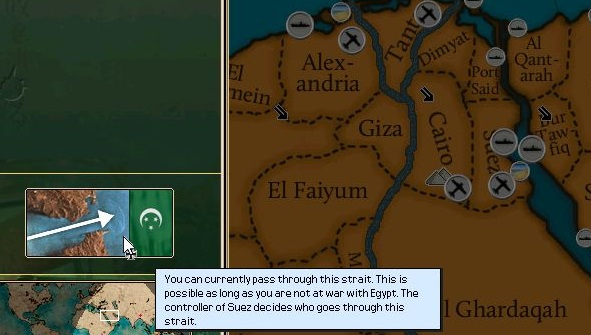

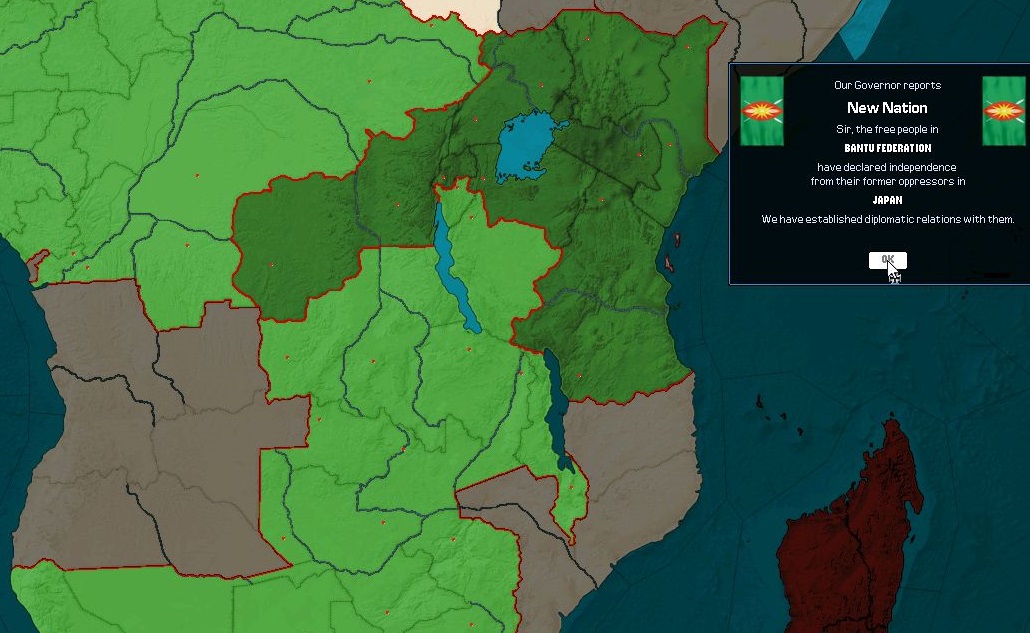

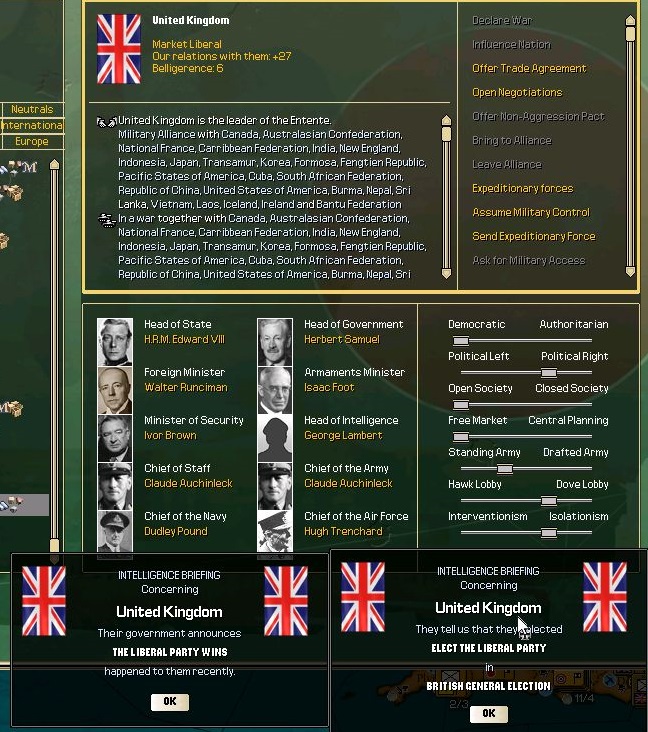

The conflict between the Internationale and the British broke out in earnest in spring 1939, as the British invaded Iceland, securing the important North Atlantic base.

They then followed up with a misinformation campaign which convinced the Entente to fortify Newfoundland. Instead, the British sailed past the heavily defended island and landed in Nova Scotia, meeting no Canadian resistance.

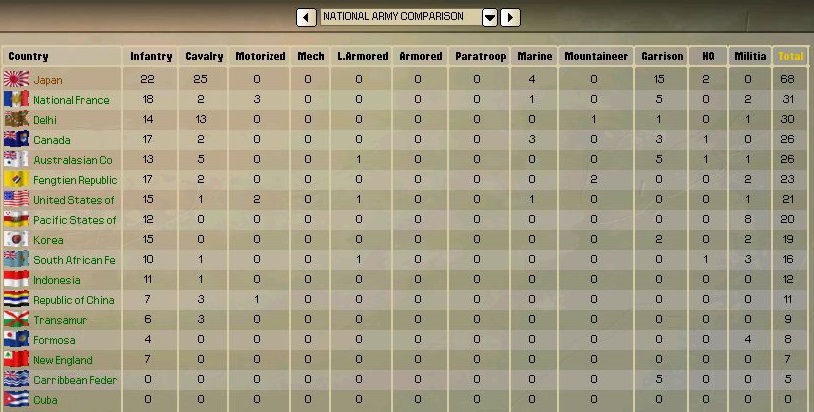

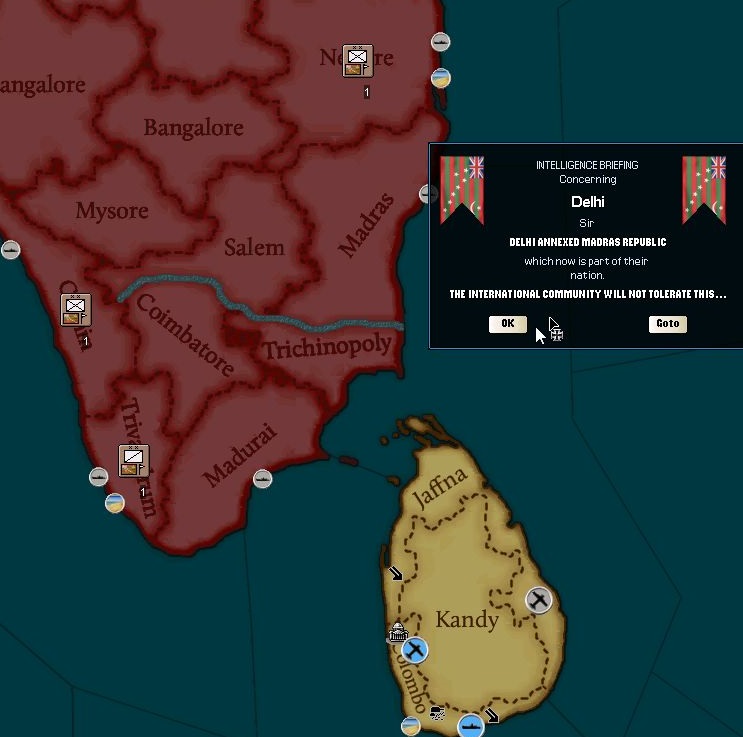

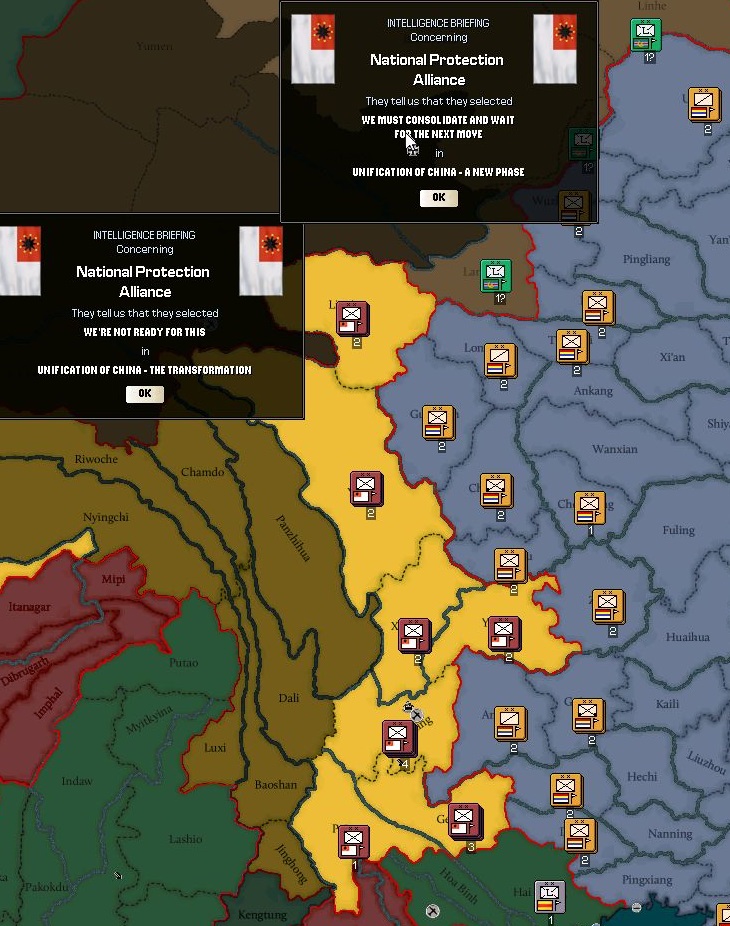

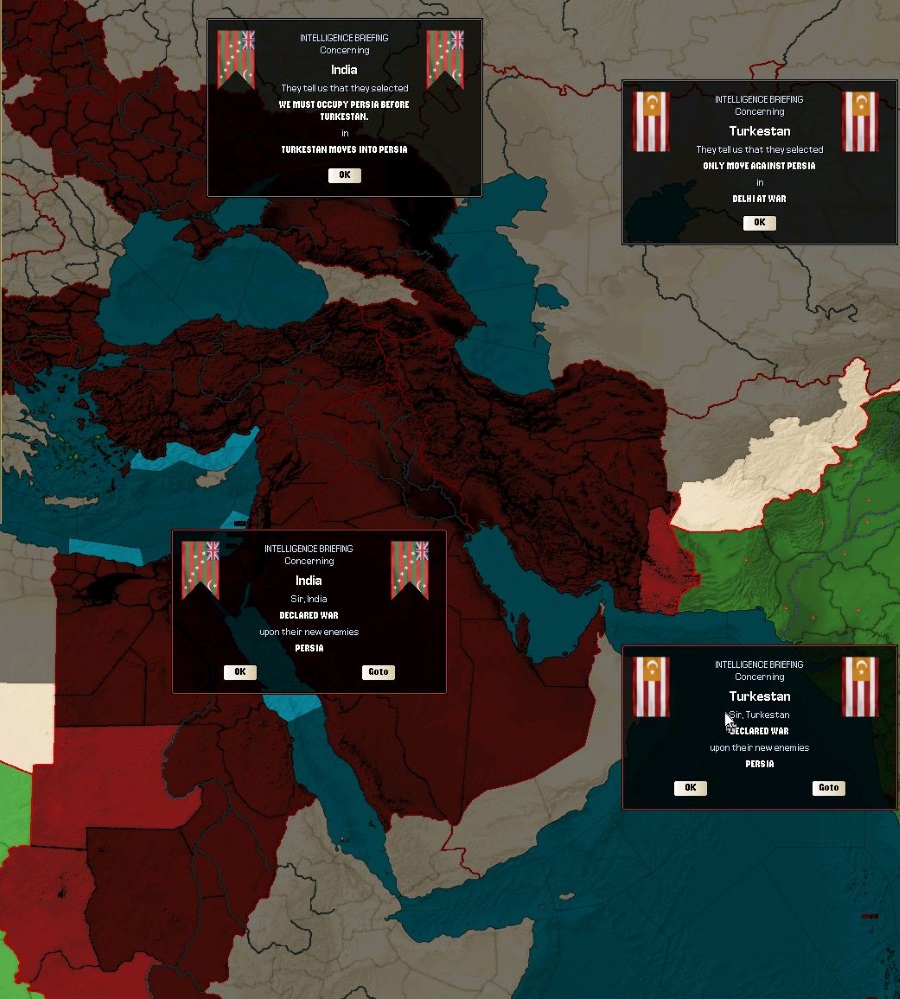

It was these developments that convinced the Shadow Council, which had voted to assist both Delhi and Canada, to prioritize assistance to Canada.

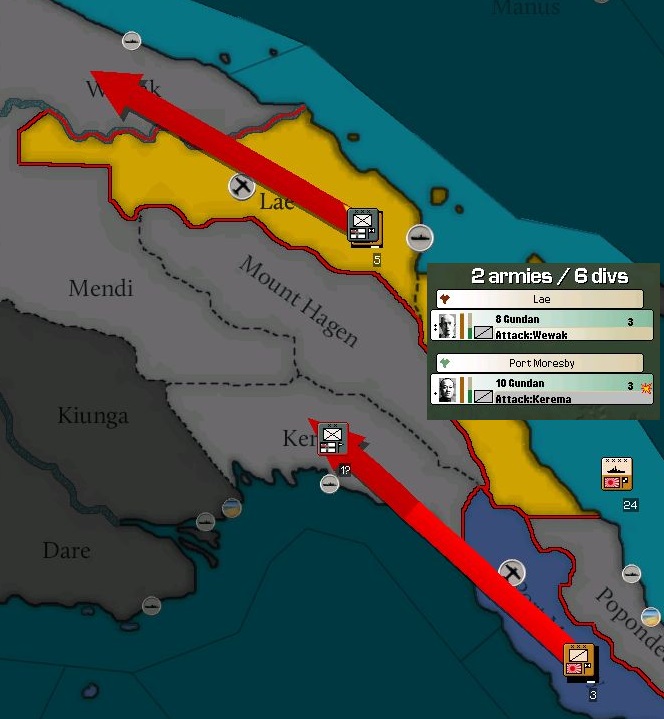

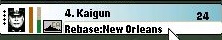

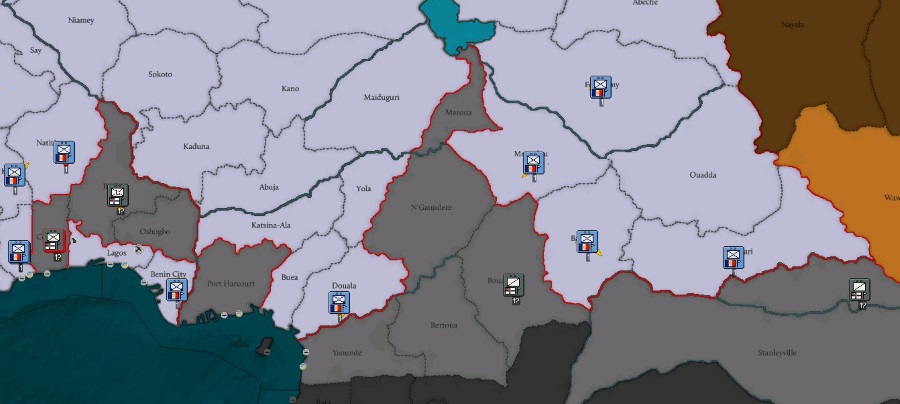

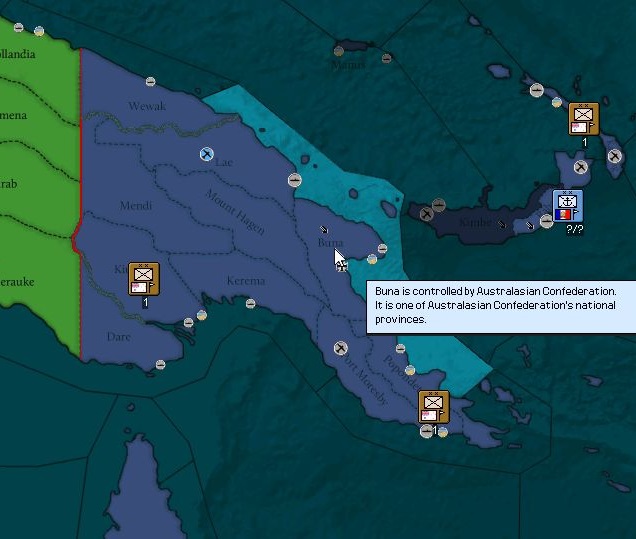

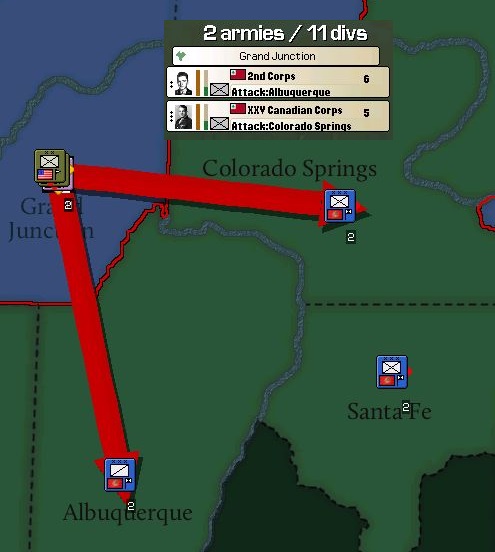

The first units of the Japanese Expeditionary Force, after sailing to Alaska (to avoid enemy naval patrols), embarked trains to Fargo, North Dakota.

The appearance of thousands of Japanese troops in Fargo was a bizarre event, but for the most part the locals were welcoming of the visitors, especially as the forces of the Pacific States were stretched thin.

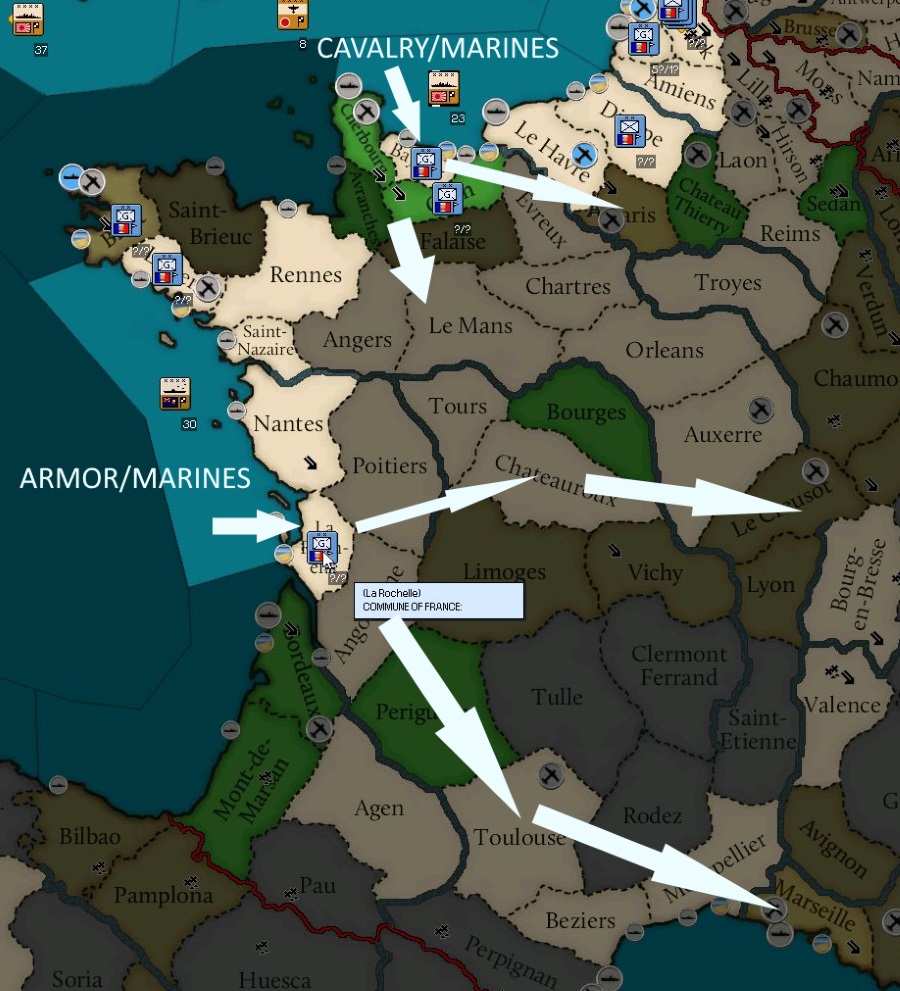

The second voyage from Japan brought two of Japan’s three cavalry corps, and these forces were dispatched to Montreal in order to defend against the British invasion of the Atlantic provinces.

After a brief stay in Fargo to regroup after the long trip, the Japanese Expeditionary Force – Midwest was dispatched to Nebraska, where they began their assault across the Missouri River.

The syndicalist defenders lacked in experience and equipment what they had in bravery and commitment, and the numerically superior veteran Japanese forces easily forced a retreat.

The JEF-MW struck south, crossing the Missouri for the second time, towards Springfield.

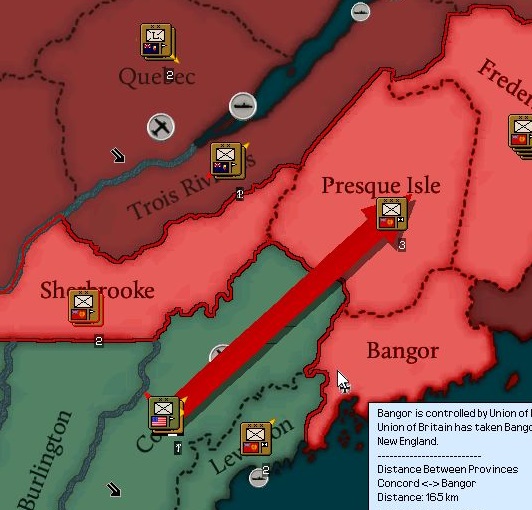

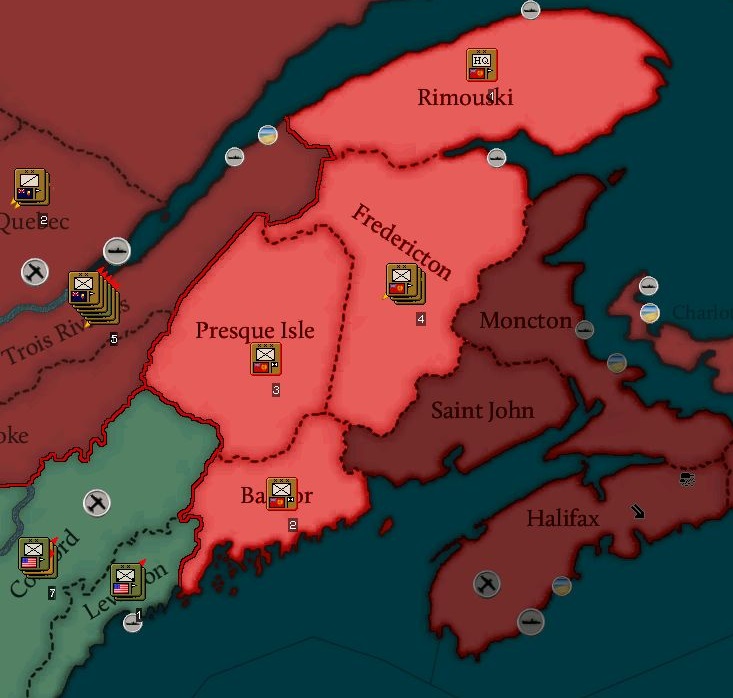

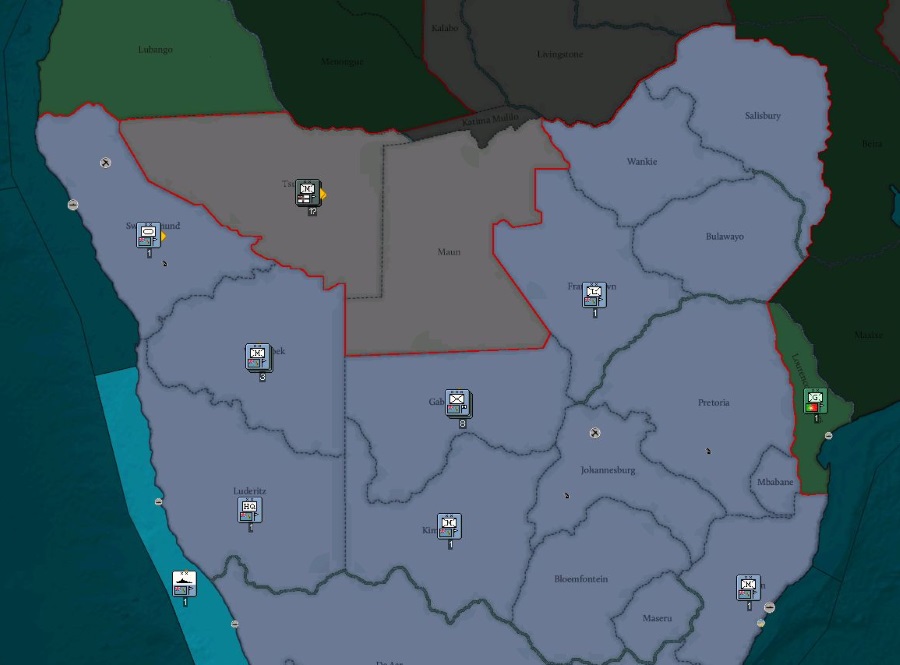

The Japanese Expeditionary Force – Atlantic Canada, arrived in Montreal in the nick of time to shore up the city’s defenses against the British, who had already captured Quebec City.

The British, accustomed to light and disorganized Canadian resistance, were unprepared for the large and rapid Japanese force which arrived to repel them.

JEF-AC split in two and advanced upon the city. One force rapidly moved to retake the southern bank of the St. Lawrence River, while the other prepared in Montreal.

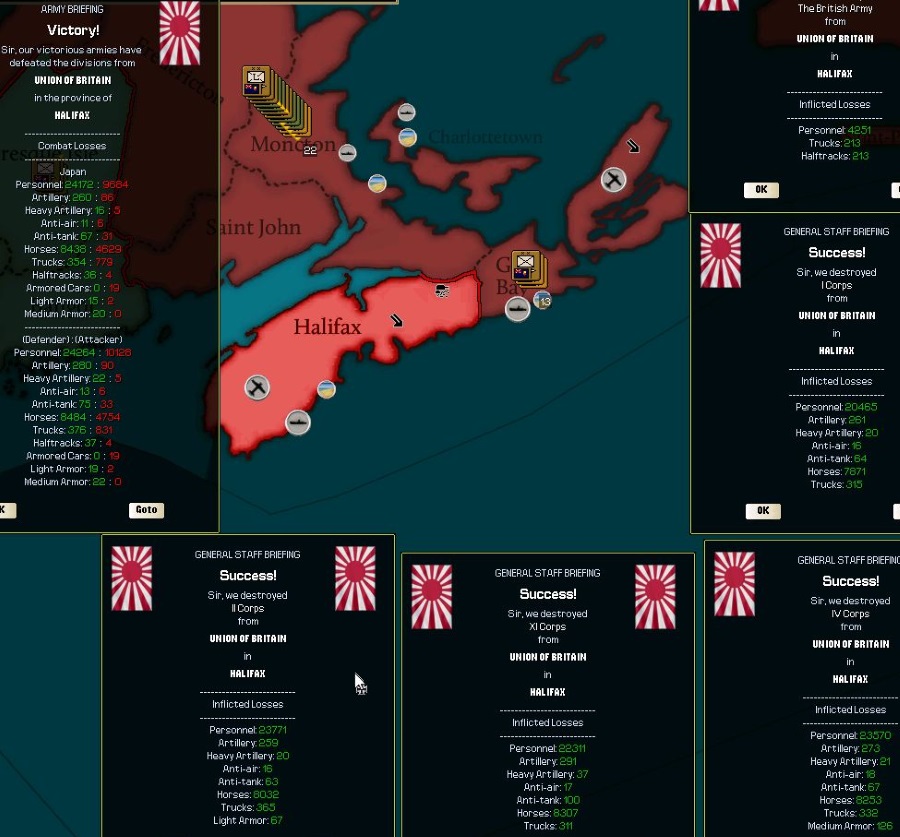

Surrounded and outnumbered, the British lost well over sixty thousand troops in the Quebec Debacle, as it would be called in London. For a nation that invested heavily in its navy and relatively little in its army, the loss of five divisions was a tremendous blow.

The forces destroyed in Quebec represented just under half of the British invasion force, and the Japanese were eager to destroy the rest. With Canadian armor counterattacking from Maine, one half of JEF-AC struck from the northwest.

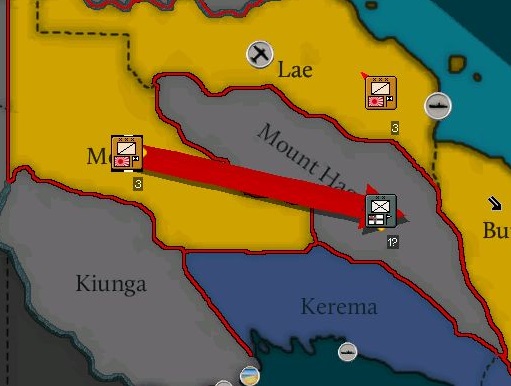

Meanwhile in the Midwest, JEF-MW was split into two. The poor quality of the syndicalist militias meant they could be easily beaten back by the skilled Japanese professionals. St. Louis fell easily, a demoralizing loss for the Combined Syndicates.

The bad news continued for the Internationale as two more British infantry divisions were isolated and destroyed on the Gaspé Peninsula.

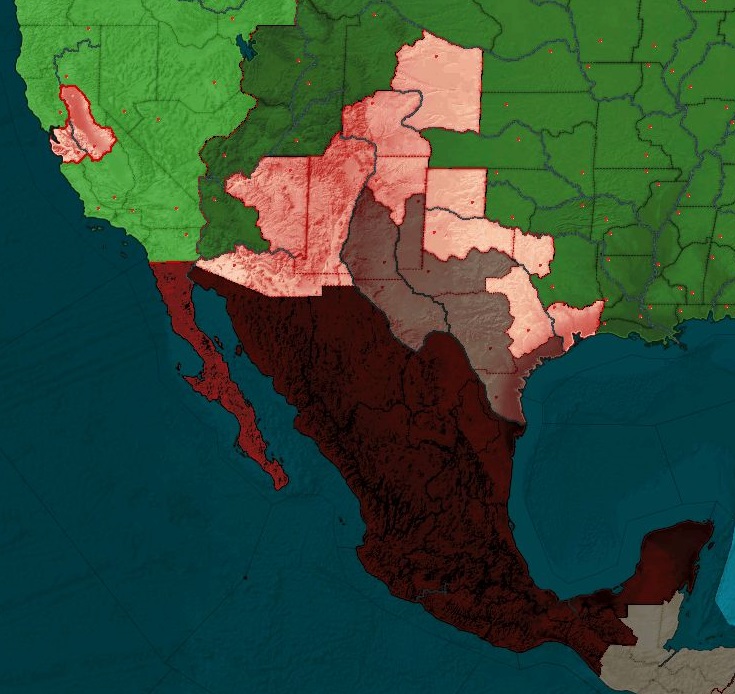

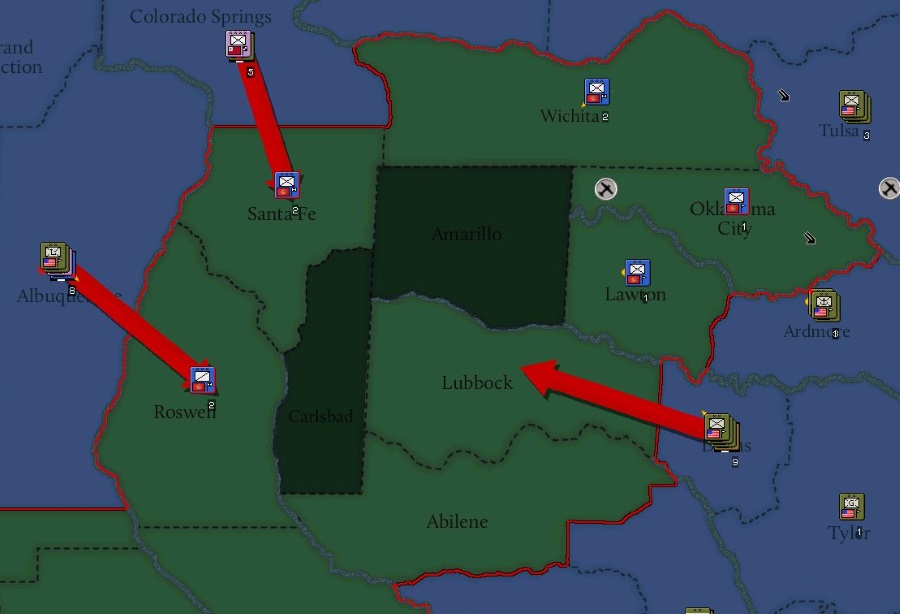

The JEF-MW’s capture of Saint Louis revealed an enormous shortcoming in the syndicalist’s defenses. By splitting the forces of Missouri in two, the Japanese were able to push half west, trapping them in Oklahoma. While their co-ideologues in Mexico sympathized with their plight, they were unwilling to risk the protection that their neutral status provided and so did not assist them. The other half of the defenses were pushed into Illinois, while Canadian cavalry began to push south into undefended Arkansas.

With the enemy divided, the path to Chicago lay open.

Meanwhile, half of JEF-AC was split off and reassigned to become the Japanese Expeditionary Force – New England. The Entente had captured New York in the first days of the war, and now Japanese cavalry was marching down Broadway.

JEF-NE began their assault through a mad cavalry rush across the George Washington Bridge. After a few weeks of stalemate as the opposing sides exchanged token fire and raids across the Hudson, the syndicalists had been expecting such a bold maneuver.

The reassignment of JEF-NE weakened JEF-AC, and so the Japanese were forced to give up some ground to the British.

The temporary setback was not a disaster, as the British were still bottled up and contained in Nova Scotia and Maine. However, the setback was worth it, as the industrial centers of Newark and northern New Jersey fell to the Entente.

The maneuverability of the Japanese cavalry, along with the well-developed infrastructure of the American Northeast, made it possible for the Japanese to rapidly advance into Philadelphia and then Baltimore, threatening the creation of a pocket in Pennsylvania.

The temporary setback in the Maritimes was reversed as the slower Canadian infantry finally caught up with the Japanese cavalry and halted the British counterattack. By holding the gateway to Nova Scotia, the Entente was able to prevent the British forces in southern New Brunswick from retreating to a position of strength in Nova Scotia. Two more British divisions were lost.

The Japanese advance was Baltimore was halted by the appearance of elite syndicalist infantry. Though it was possible that the Japanese could have forced their way past the enemy, Koji Sakai’s doctrines held that the Japanese should not be fighting bloody battles if they had another choice, and so they elected to hold their position in Philadelphia and allow Entente infantry to reinforce their positions in New Jersey.

The enemy’s morale was badly shaken when Canadian infantry marched into Chicago, forcing the Reed regime to flee to the abandoned Washington offices of the United States government they had defeated only a few years prior.

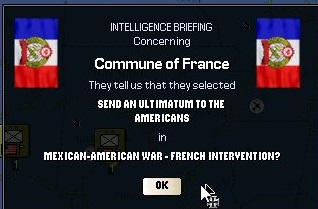

As Chicago fell, a major controversy erupted as Mexico denied the Combined Syndicates permission for their troops to flee across the border. The Communal government in Paris was irritated that a socialist nation would abandon their co-ideologues, but Mexico was about to find itself very much alone in North America, and so wisely elected not to antagonize the Entente.

With the Oklahoma pocket destroyed, JEF-MW decided to begin an advance southwards towards New Orleans.

And in the east, JEF-NE began a renewed assault on Baltimore. Japan had turned the tide in North America, and it was doubtful that the syndicalists would survive the winter.

No votes, as the next update is contemporaneous with this one. Votes for further policy will occur at the next update.

The conflict between the Internationale and the British broke out in earnest in spring 1939, as the British invaded Iceland, securing the important North Atlantic base.

They then followed up with a misinformation campaign which convinced the Entente to fortify Newfoundland. Instead, the British sailed past the heavily defended island and landed in Nova Scotia, meeting no Canadian resistance.

It was these developments that convinced the Shadow Council, which had voted to assist both Delhi and Canada, to prioritize assistance to Canada.

The first units of the Japanese Expeditionary Force, after sailing to Alaska (to avoid enemy naval patrols), embarked trains to Fargo, North Dakota.

The appearance of thousands of Japanese troops in Fargo was a bizarre event, but for the most part the locals were welcoming of the visitors, especially as the forces of the Pacific States were stretched thin.

The second voyage from Japan brought two of Japan’s three cavalry corps, and these forces were dispatched to Montreal in order to defend against the British invasion of the Atlantic provinces.

After a brief stay in Fargo to regroup after the long trip, the Japanese Expeditionary Force – Midwest was dispatched to Nebraska, where they began their assault across the Missouri River.

The syndicalist defenders lacked in experience and equipment what they had in bravery and commitment, and the numerically superior veteran Japanese forces easily forced a retreat.

The JEF-MW struck south, crossing the Missouri for the second time, towards Springfield.

The Japanese Expeditionary Force – Atlantic Canada, arrived in Montreal in the nick of time to shore up the city’s defenses against the British, who had already captured Quebec City.

The British, accustomed to light and disorganized Canadian resistance, were unprepared for the large and rapid Japanese force which arrived to repel them.

JEF-AC split in two and advanced upon the city. One force rapidly moved to retake the southern bank of the St. Lawrence River, while the other prepared in Montreal.

Surrounded and outnumbered, the British lost well over sixty thousand troops in the Quebec Debacle, as it would be called in London. For a nation that invested heavily in its navy and relatively little in its army, the loss of five divisions was a tremendous blow.

The forces destroyed in Quebec represented just under half of the British invasion force, and the Japanese were eager to destroy the rest. With Canadian armor counterattacking from Maine, one half of JEF-AC struck from the northwest.

Meanwhile in the Midwest, JEF-MW was split into two. The poor quality of the syndicalist militias meant they could be easily beaten back by the skilled Japanese professionals. St. Louis fell easily, a demoralizing loss for the Combined Syndicates.

The bad news continued for the Internationale as two more British infantry divisions were isolated and destroyed on the Gaspé Peninsula.

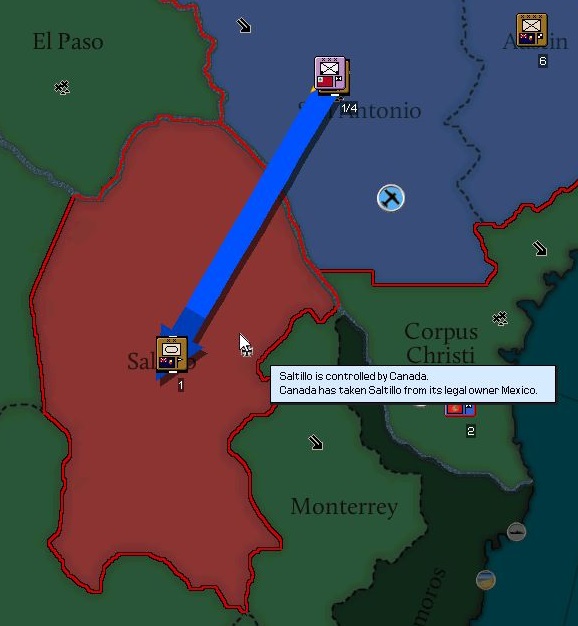

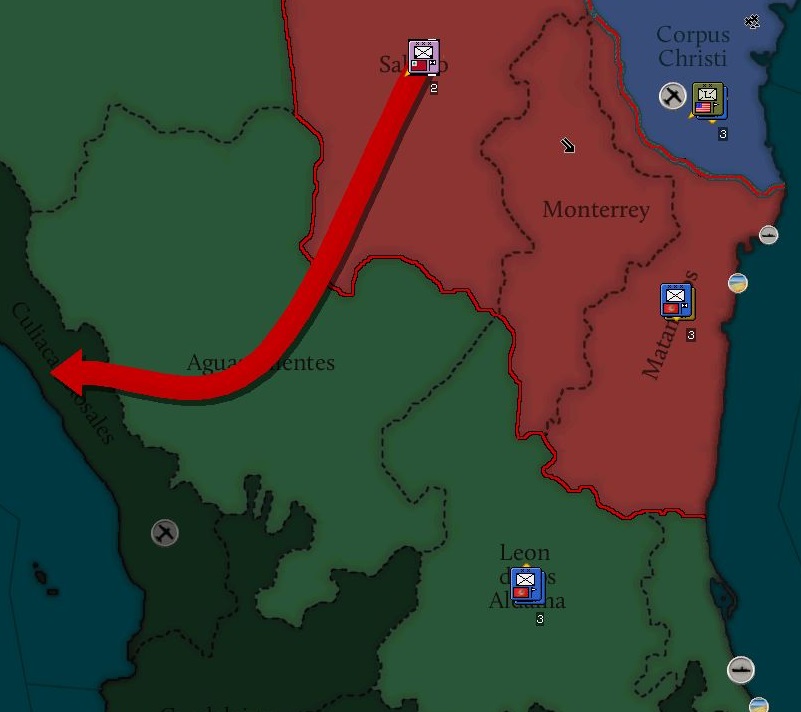

The JEF-MW’s capture of Saint Louis revealed an enormous shortcoming in the syndicalist’s defenses. By splitting the forces of Missouri in two, the Japanese were able to push half west, trapping them in Oklahoma. While their co-ideologues in Mexico sympathized with their plight, they were unwilling to risk the protection that their neutral status provided and so did not assist them. The other half of the defenses were pushed into Illinois, while Canadian cavalry began to push south into undefended Arkansas.

With the enemy divided, the path to Chicago lay open.

Meanwhile, half of JEF-AC was split off and reassigned to become the Japanese Expeditionary Force – New England. The Entente had captured New York in the first days of the war, and now Japanese cavalry was marching down Broadway.

JEF-NE began their assault through a mad cavalry rush across the George Washington Bridge. After a few weeks of stalemate as the opposing sides exchanged token fire and raids across the Hudson, the syndicalists had been expecting such a bold maneuver.

The reassignment of JEF-NE weakened JEF-AC, and so the Japanese were forced to give up some ground to the British.

The temporary setback was not a disaster, as the British were still bottled up and contained in Nova Scotia and Maine. However, the setback was worth it, as the industrial centers of Newark and northern New Jersey fell to the Entente.

The maneuverability of the Japanese cavalry, along with the well-developed infrastructure of the American Northeast, made it possible for the Japanese to rapidly advance into Philadelphia and then Baltimore, threatening the creation of a pocket in Pennsylvania.

The temporary setback in the Maritimes was reversed as the slower Canadian infantry finally caught up with the Japanese cavalry and halted the British counterattack. By holding the gateway to Nova Scotia, the Entente was able to prevent the British forces in southern New Brunswick from retreating to a position of strength in Nova Scotia. Two more British divisions were lost.

The Japanese advance was Baltimore was halted by the appearance of elite syndicalist infantry. Though it was possible that the Japanese could have forced their way past the enemy, Koji Sakai’s doctrines held that the Japanese should not be fighting bloody battles if they had another choice, and so they elected to hold their position in Philadelphia and allow Entente infantry to reinforce their positions in New Jersey.

The enemy’s morale was badly shaken when Canadian infantry marched into Chicago, forcing the Reed regime to flee to the abandoned Washington offices of the United States government they had defeated only a few years prior.

As Chicago fell, a major controversy erupted as Mexico denied the Combined Syndicates permission for their troops to flee across the border. The Communal government in Paris was irritated that a socialist nation would abandon their co-ideologues, but Mexico was about to find itself very much alone in North America, and so wisely elected not to antagonize the Entente.

With the Oklahoma pocket destroyed, JEF-MW decided to begin an advance southwards towards New Orleans.

And in the east, JEF-NE began a renewed assault on Baltimore. Japan had turned the tide in North America, and it was doubtful that the syndicalists would survive the winter.

No votes, as the next update is contemporaneous with this one. Votes for further policy will occur at the next update.