Chief Savage Man

Active member

Chapter Twenty Four: Operation Shogun (April 16 – July 26, 1942)

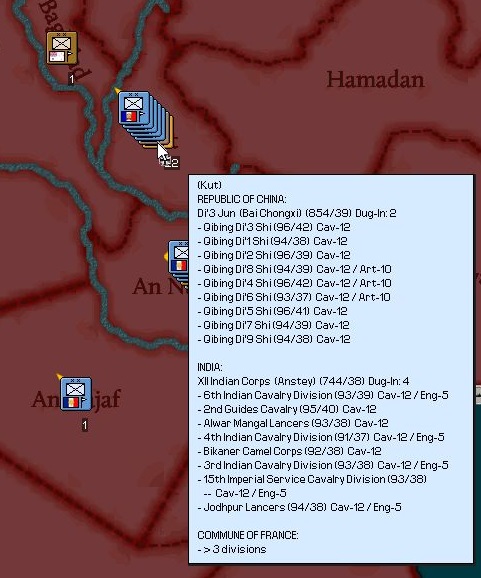

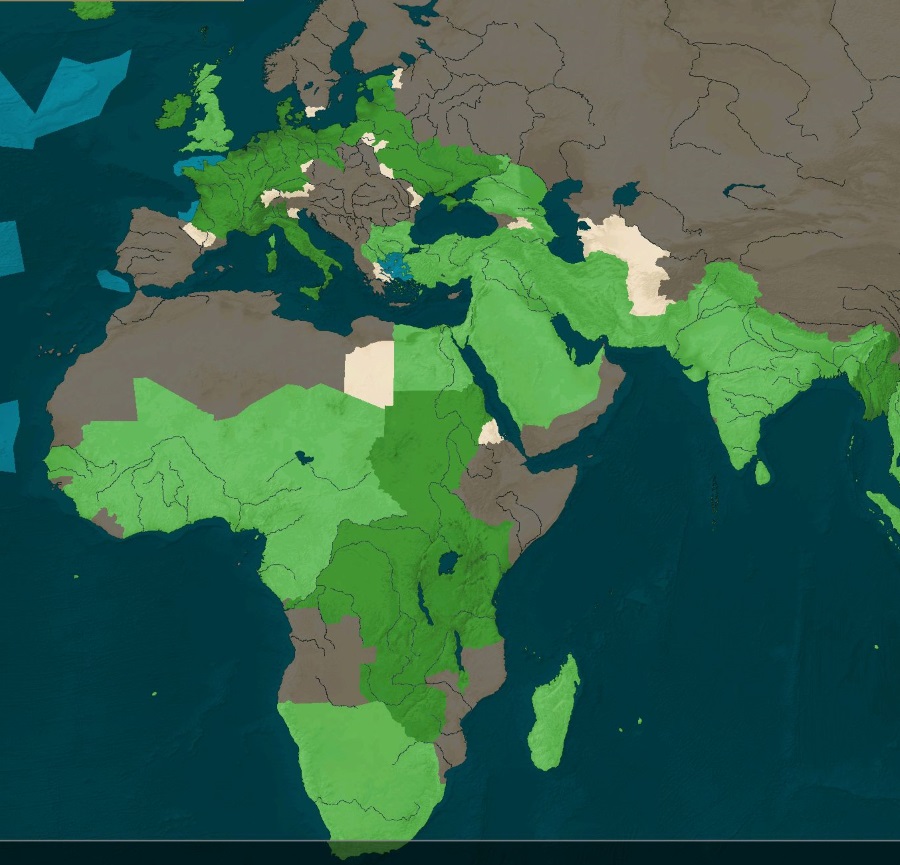

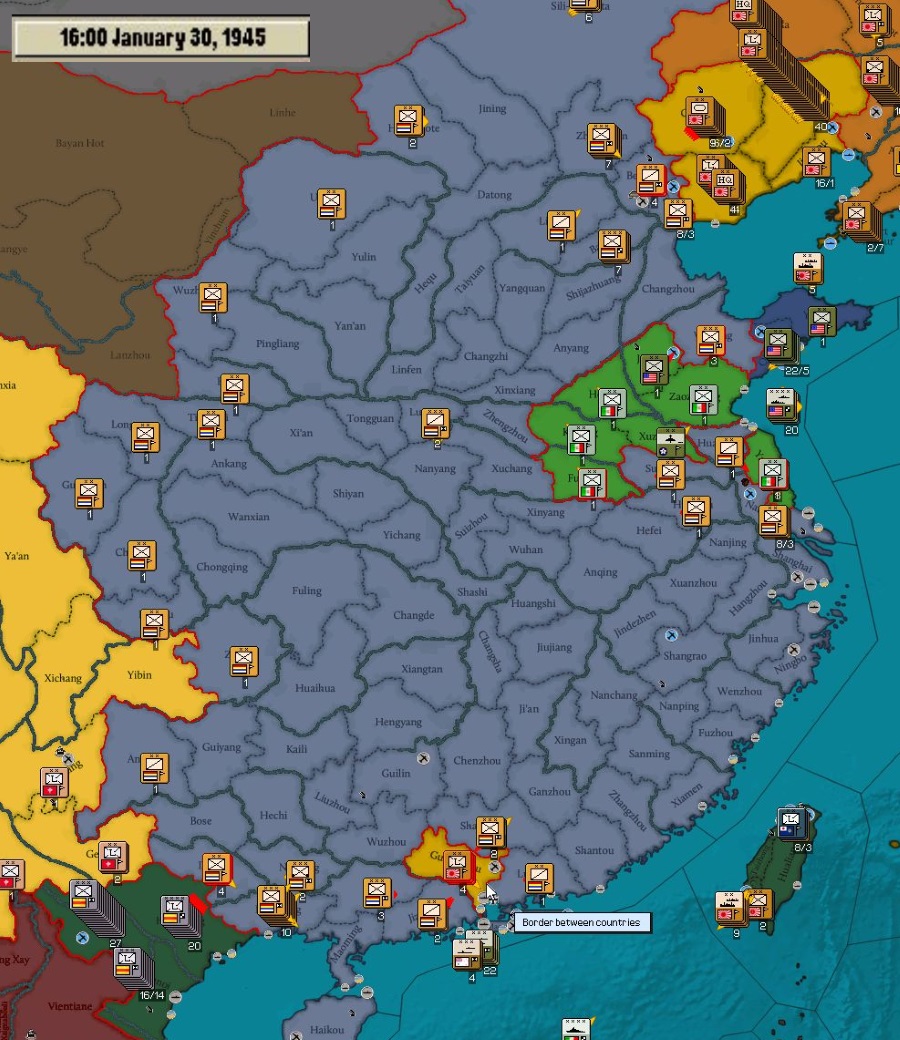

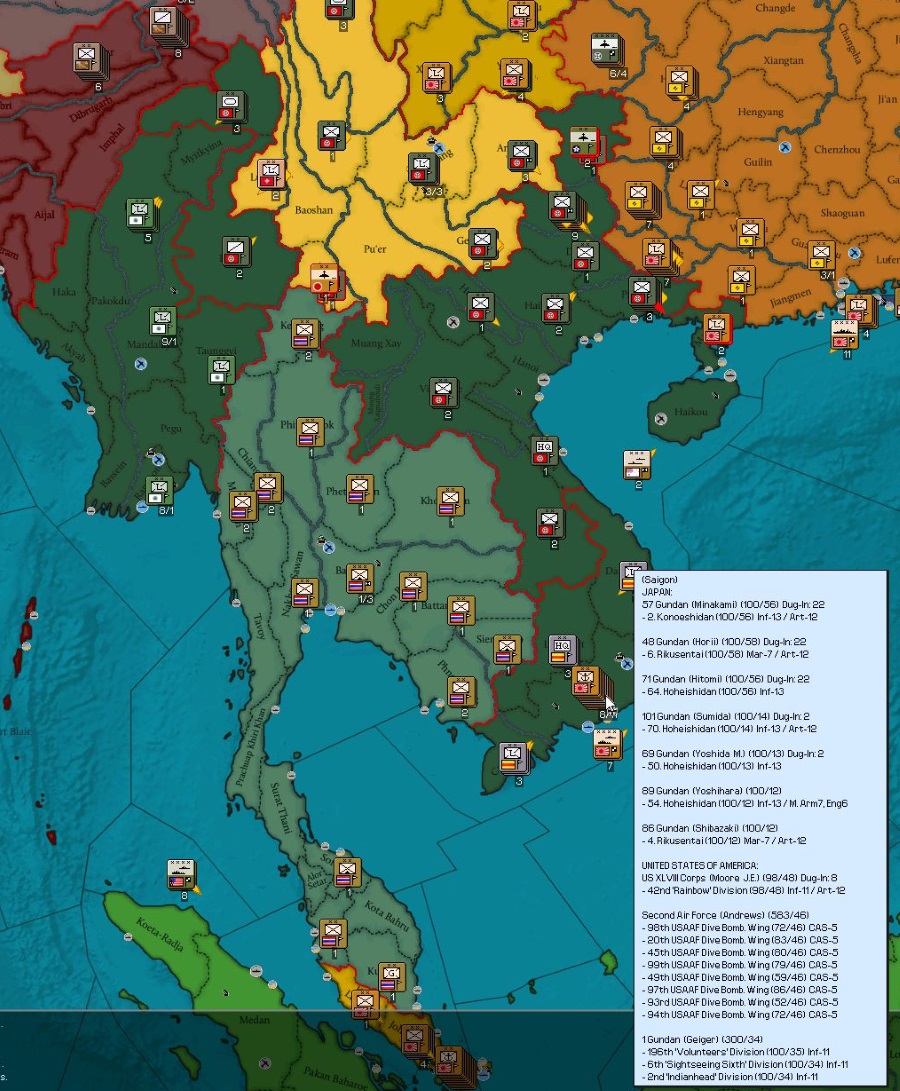

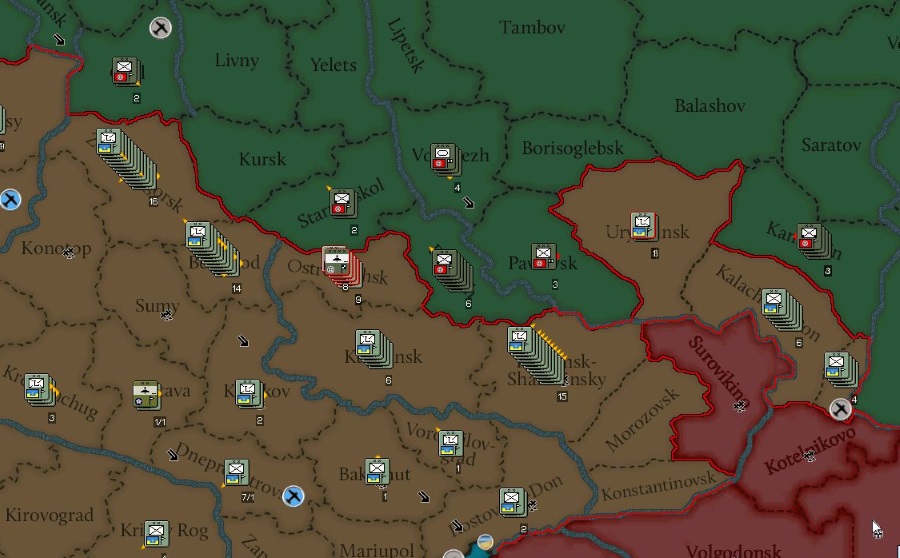

Entente planners knew that they would not be able to hide the preparations for the assault on Europe forever, but their luck had held through April. French strategic thought had been focused on the pursuit of a massive offensive into the Middle East, to gain oil lost after the recapture of Texas and to try and deny resources to the ever growing Entente industrial base that was bound to outproduce the Internationale in the long run. The arrival of over a hundred Entente divisions forced a stalemate instead. The French knew that a massive force was in their path, but what were not so sure about what national armies were most prevalent in the Eastern Command.

This began to change when the French made their first attempt at breaking the lines in Iraq. The experienced French commanders and veteran troops believed they had a good chance of breaking through the enemy line.

Their expertise was thwarted by the sheer scale of the defensive fortifications around Karbala that had been built in the weeks since the two armies had settled into the stalemate.

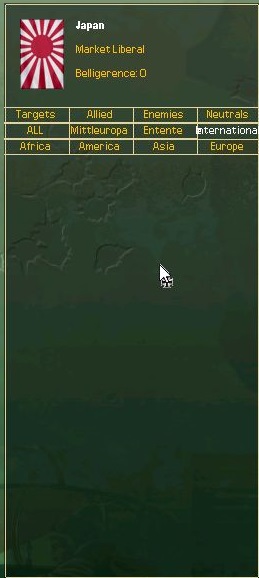

The French called off their first attack on Karbala after just a few days, having taken nearly thirty thousand casualties, including losing sixty-one tanks. What they also found was that there were hardly any Japanese or North American divisions. The French command had assumed that, based on underestimates of the size of the new Asian Entente armies, North American divisions were the ones shoring up the lines in the Middle East.

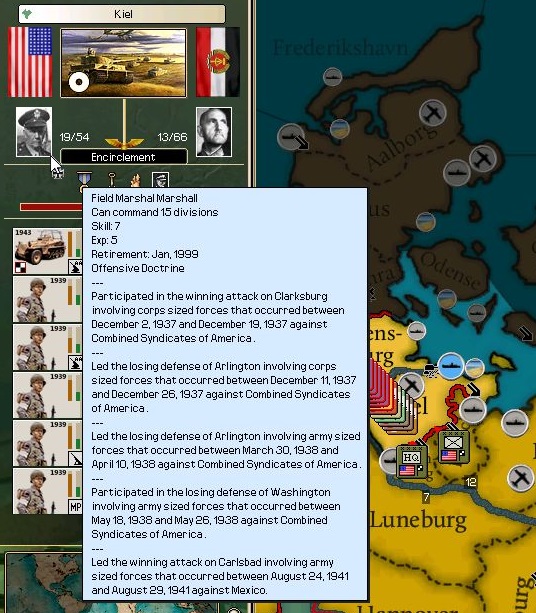

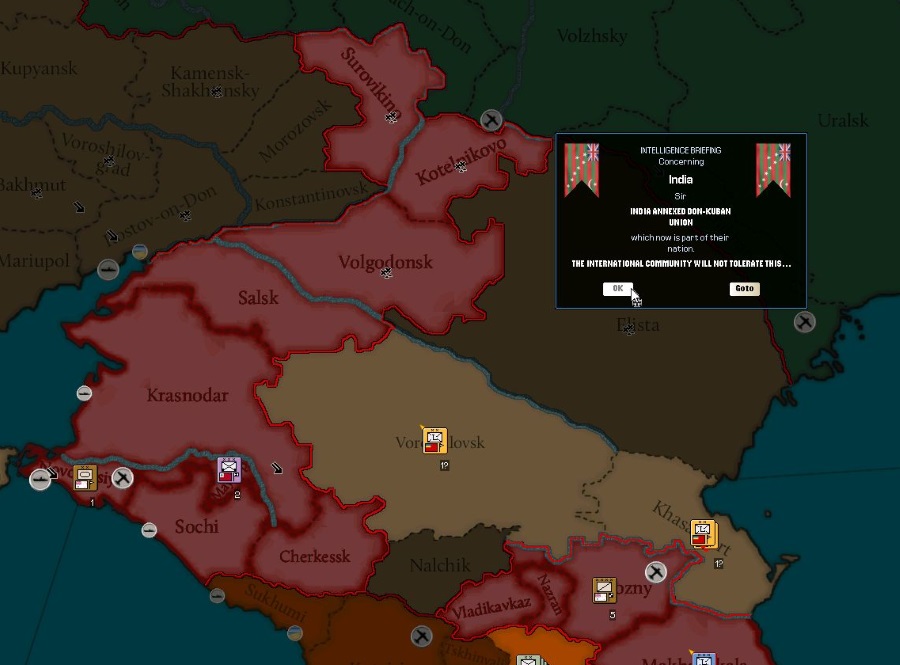

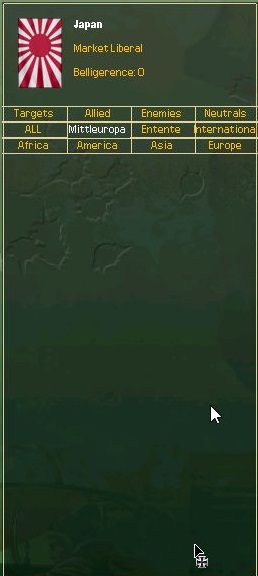

The realization that the Japanese and North American armies were not in the Middle East caused the neutral powers of the world to recognize that something was afoot. The Vozhd in particular was keen enough to see what was about to happen, and he decided that he wanted a piece of the action.

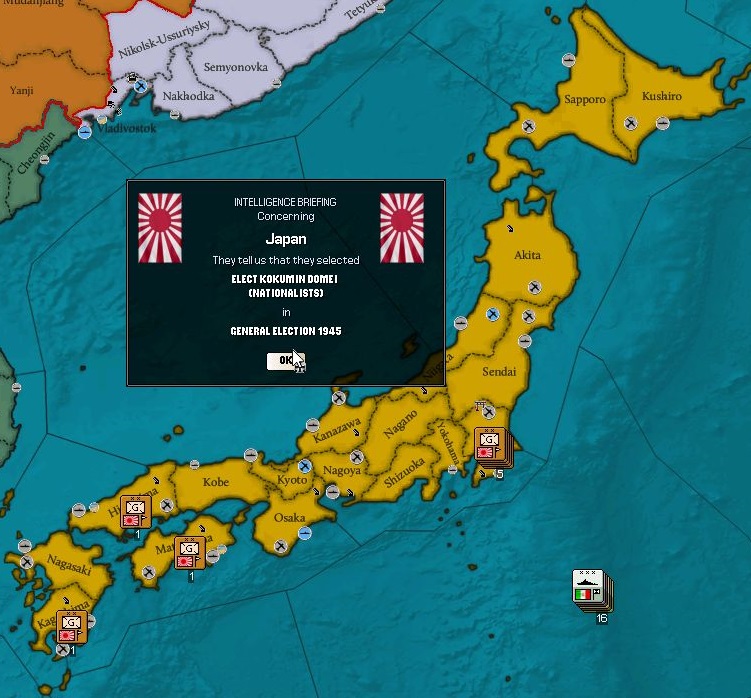

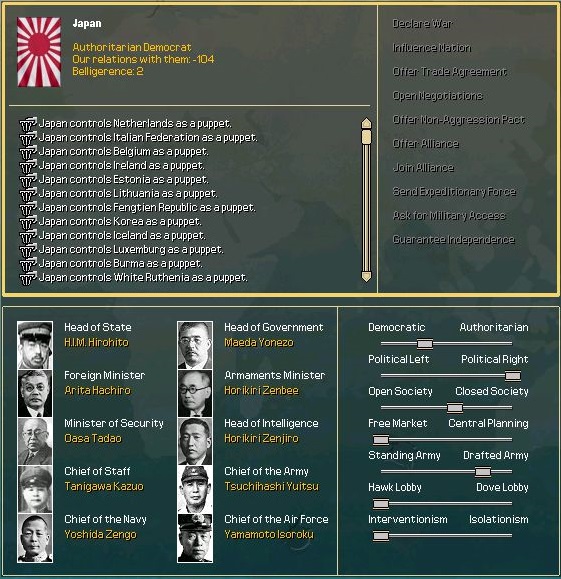

A Russian proposal for a grand bargain that would return Western Europe to the Entente while Russia would seize Eastern Europe. The Minseito absolutely refused to consider it, but also did not wish to publicly provoke Russia at that point in time, so the proposal was ignored and would remain classified until 1985.

As spring rolled into summer, the ideal invasion dates for the longest possible summer campaign came and went, as the Entente logistics network was overworked.

Finally, the Entente decided that a date needed to be set, and they decided that the invasion would launch immediately after the newest Japanese armored and motorized divisions arrived from the Home Islands, in late July. It was not optimal timing, but it would have to do.

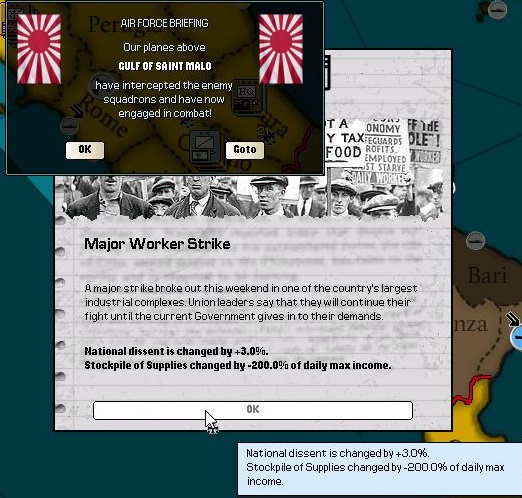

While the passage of the optimal dates led some in the Internationale to be optimistic and believe they had until 1943 to prepare for an invasion, most commanders were not fooled and resorted to novel strategies to try and put the Entente off balance for as long as possible.

The Italian raid of Alexandria served as a distraction that pulled away Indian cavalry divisions earmarked for the invasion of Persia, but the Italians did not have the naval power to support a large invasion force.

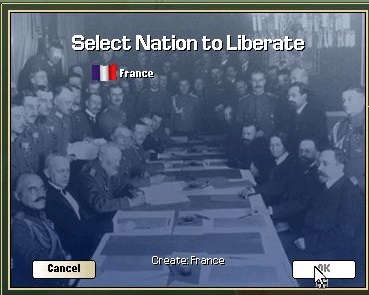

More effective for the Internationale was the continued support of the Algerian rebels who declared victory in their war of liberation after seizing Tunis. The Entente continued to shun National France especially now that they held naval bases in Egypt.

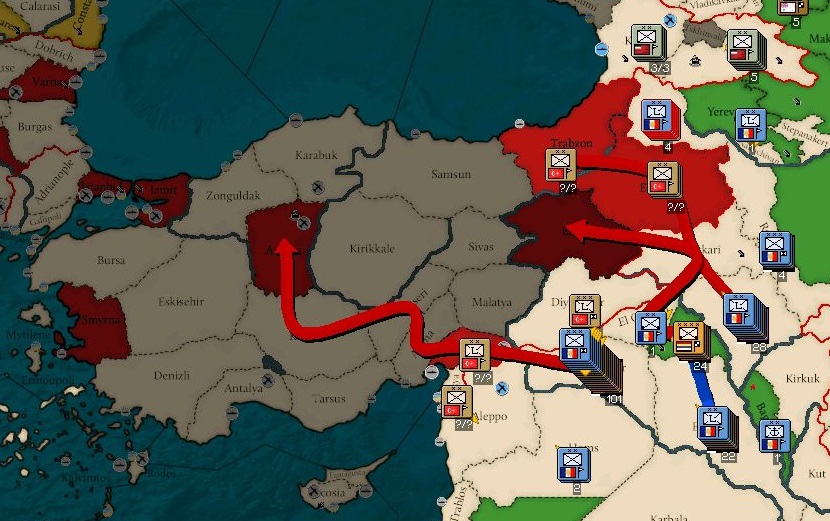

About a week before the Japanese armor was scheduled to arrive in England, the Persian Gambit was given the go ahead. The main force meant to drive to the Caucasus was about half the size as originally planned, but the arrival of more French divisions on the line in Syria meant that more of the intended invasion force had to be left where it was to hold the line.

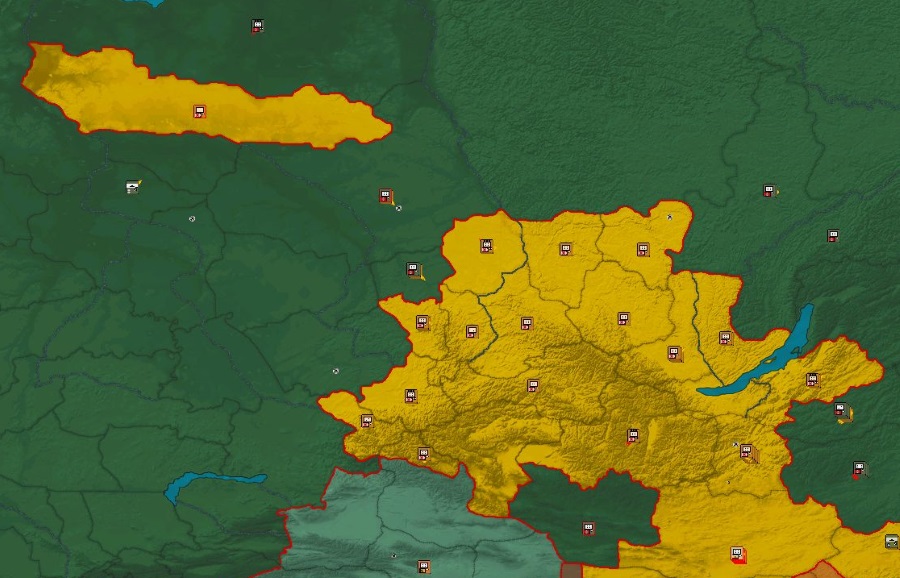

The Entente was cutting it close, as Turkestan was in a state of collapse by July.

In the end, their timing turned out to be very good, as the power of Turkestan to resist was shattered, but the Russians were not too close that they would cross the Persian border before the Entente could secure it.

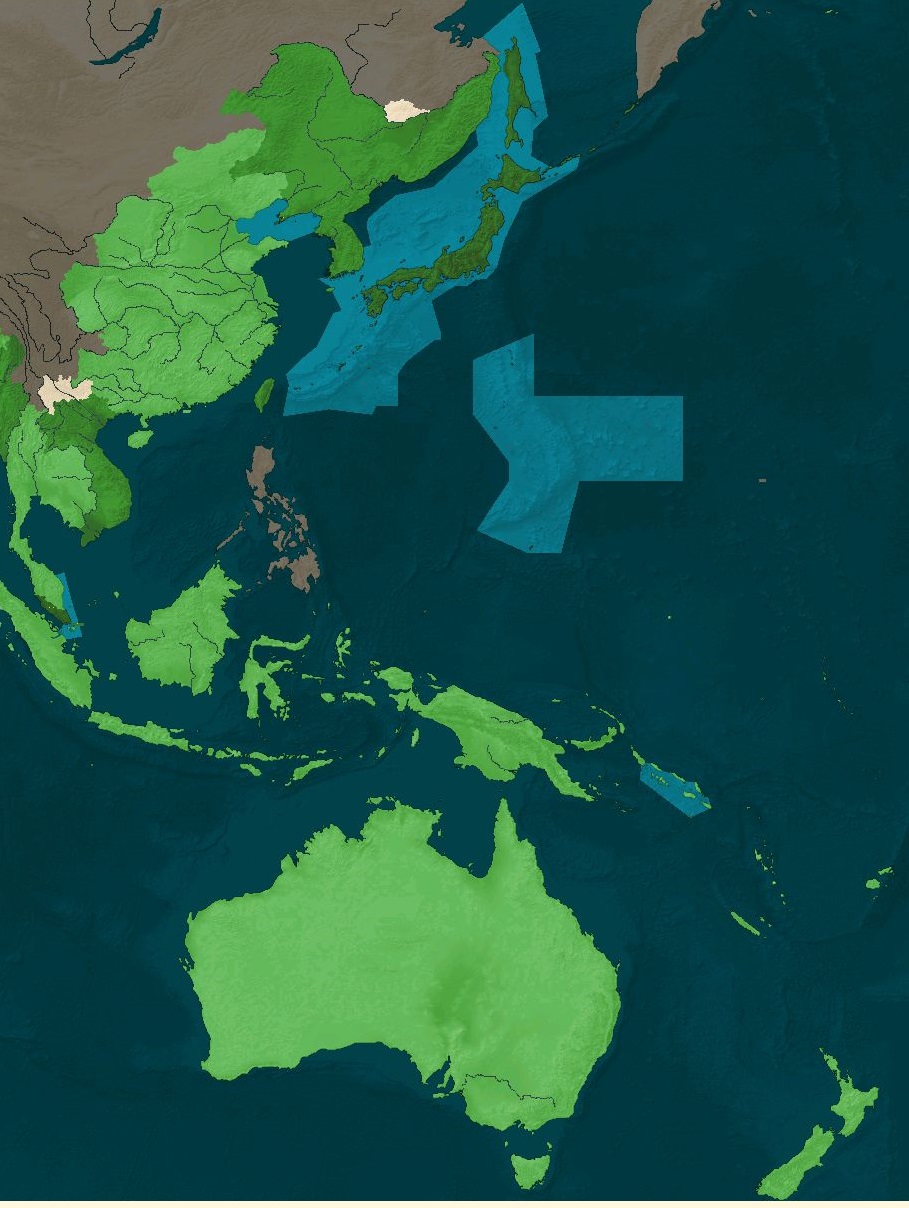

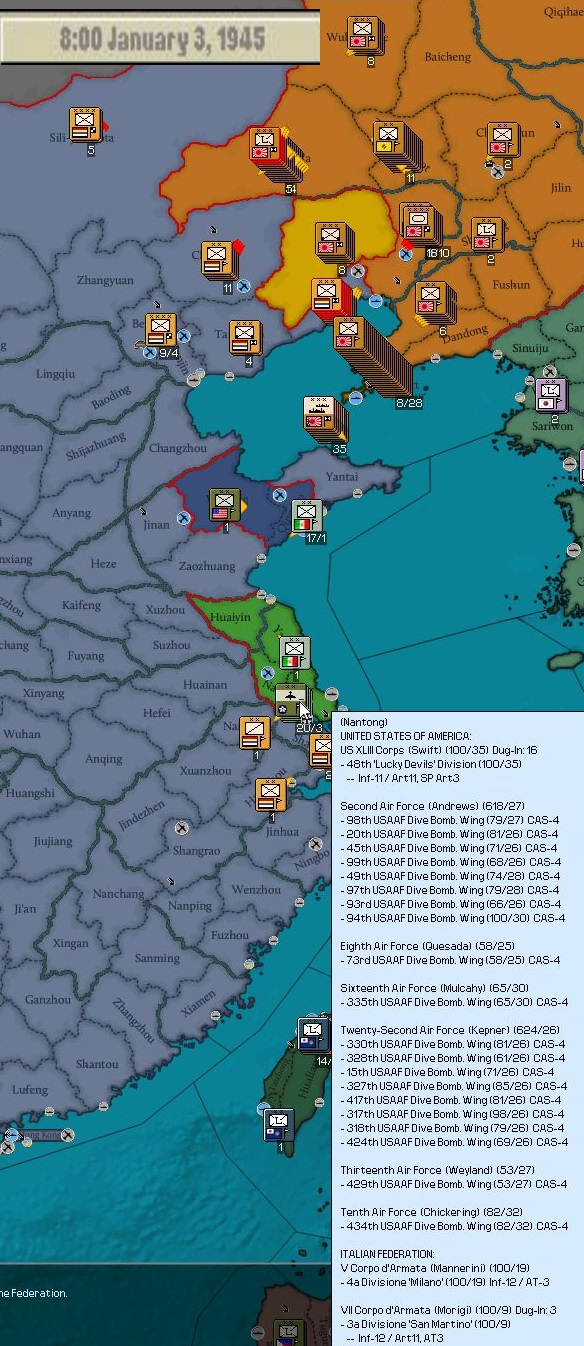

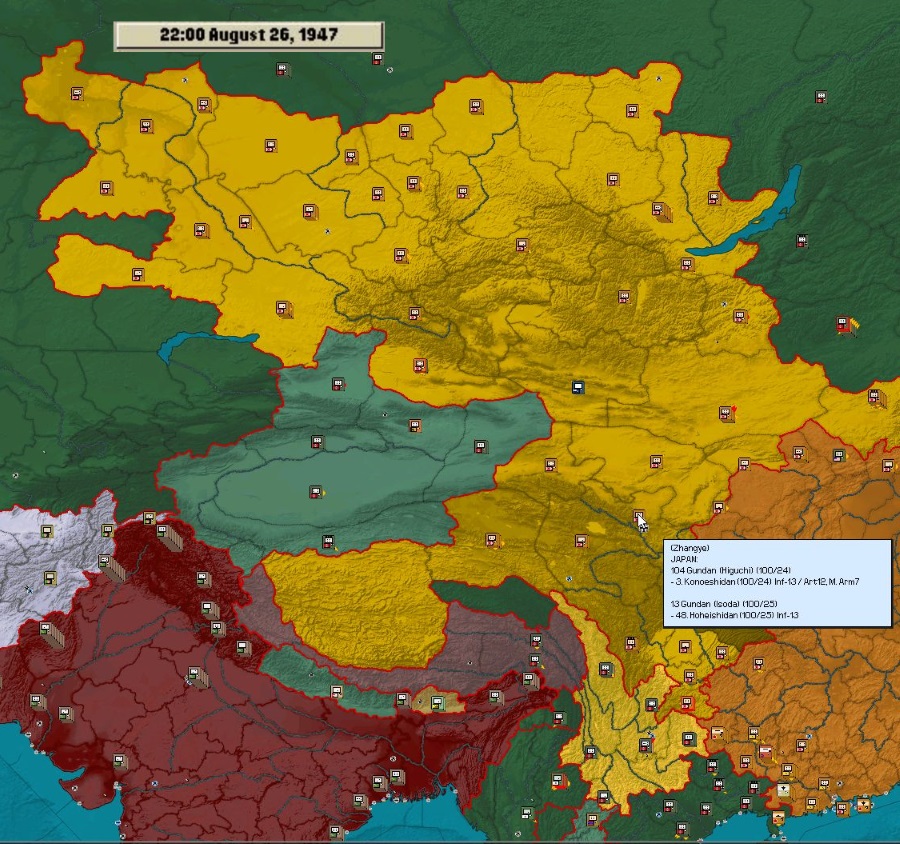

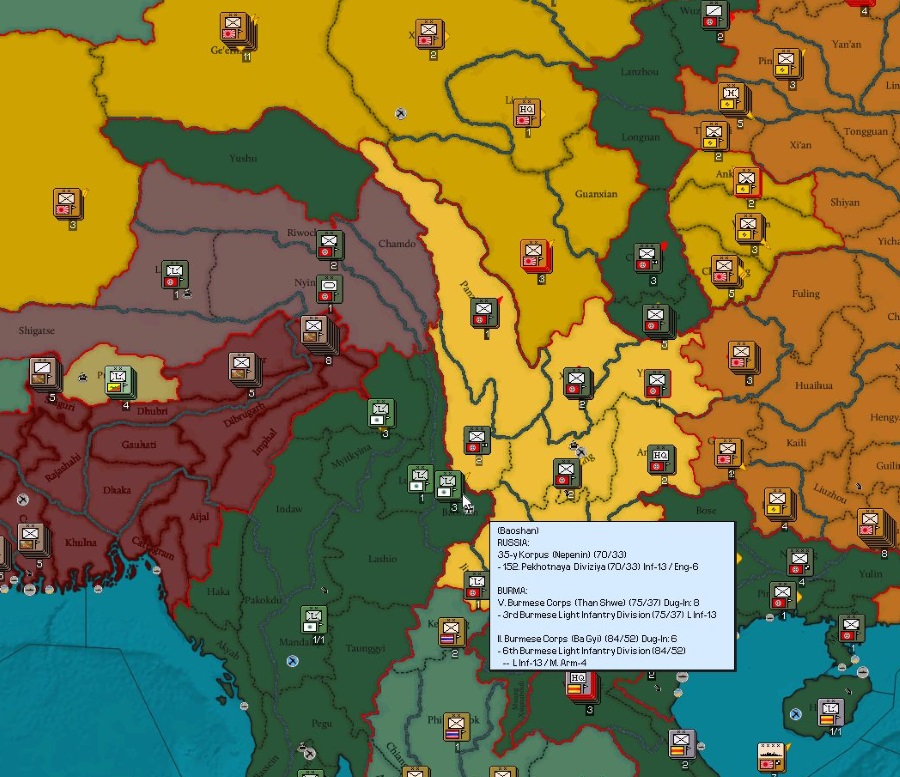

A force of Burmese, Taiwanese and Indian infantry moved to do just that, while a mobile force of Chinese, New English, Indian, Japanese and Australasian divisions struck the main blow.

Most divisions pushed northwest towards Baku, while the Chinese divisions peeled off to secure Teheran.

The only resistance the Turkestan could put up to protect their vassal was one battered infantry division pushed south by the Russians.

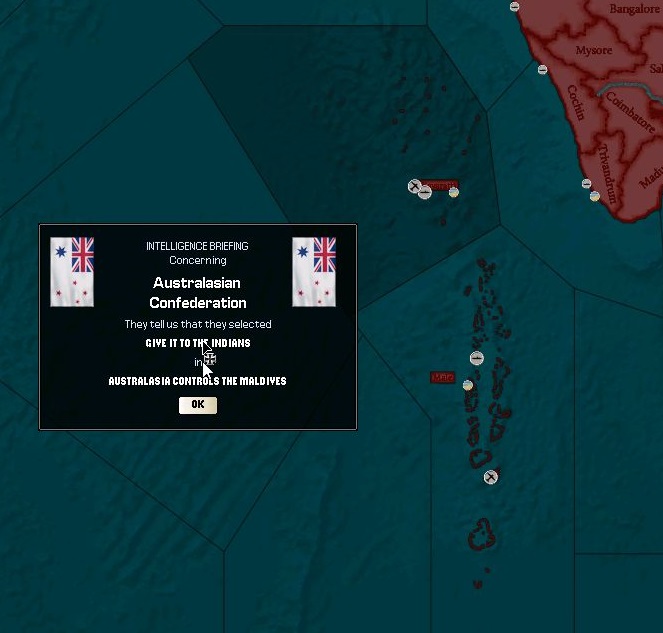

The Australasian armor pushed ahead of every other division in order to scout, and found that Azerbaijan and Armenia were virtually undefended. Every French division in the region had been sent to try and break the line in Iraq and Syria.

The Entente conquest of Persia would cost virtually no blood or treasure.

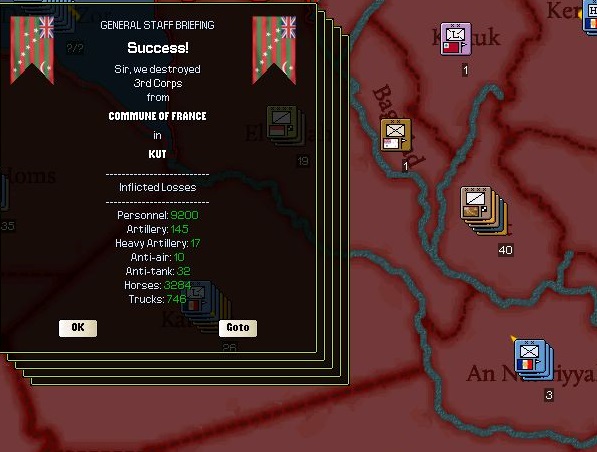

The maneuver caught the Internationale by surprise, and their attempts to break the stalemate became more aggressive. They suffered more than fifty thousand casualties in a second attempt to take Karbala.

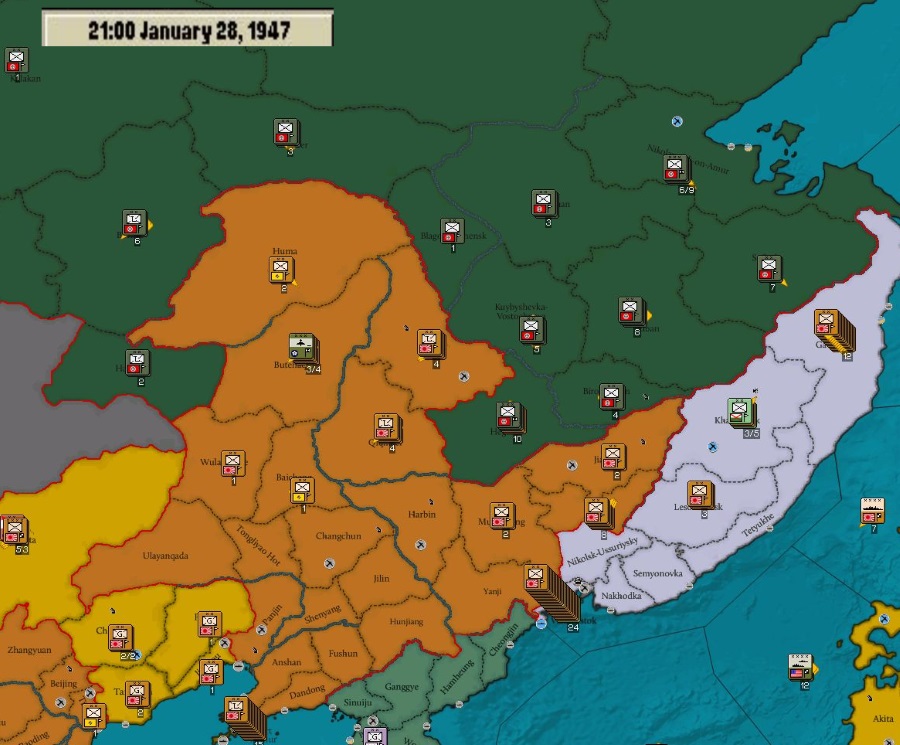

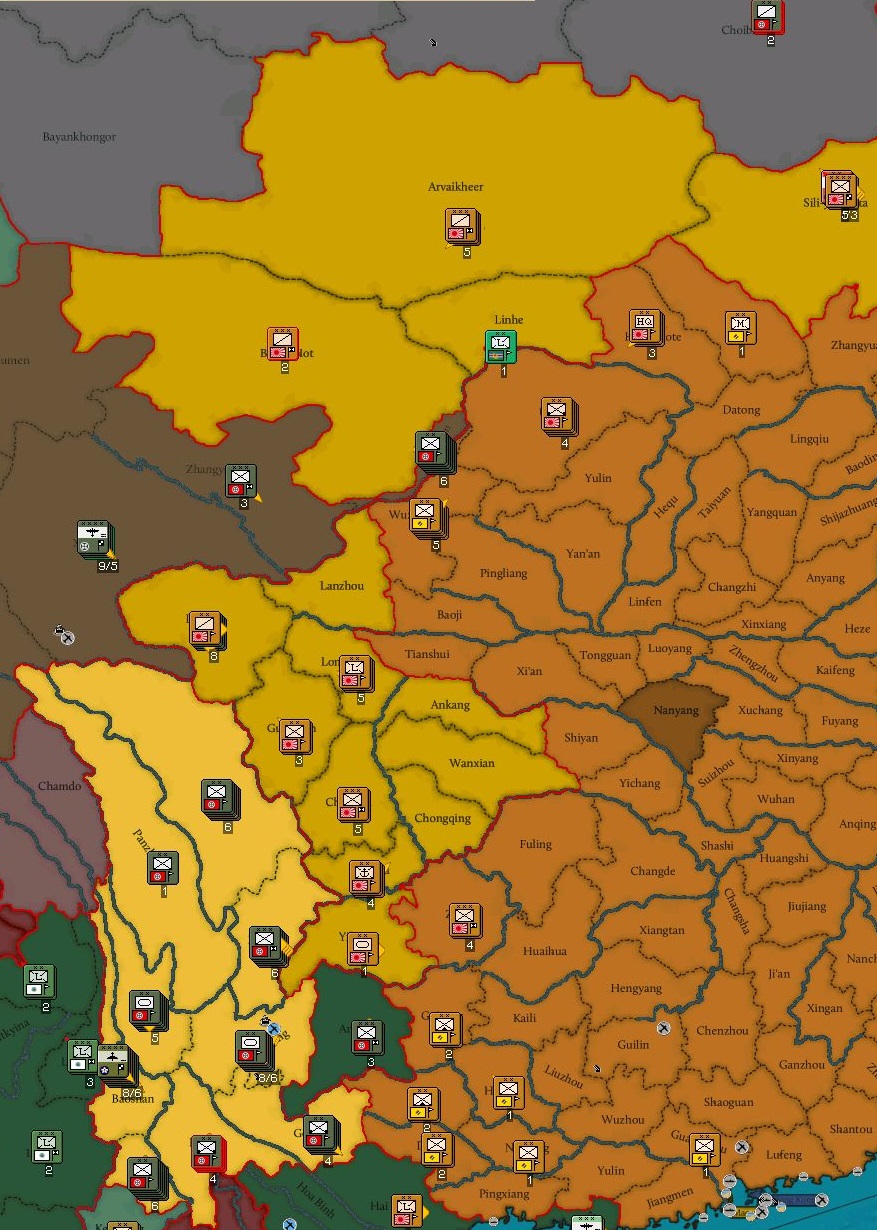

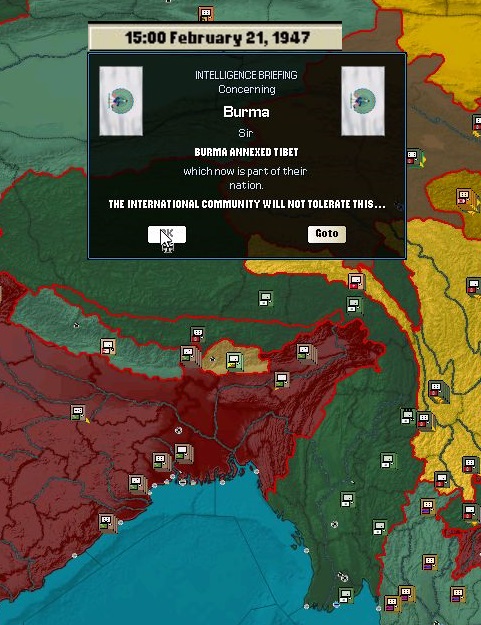

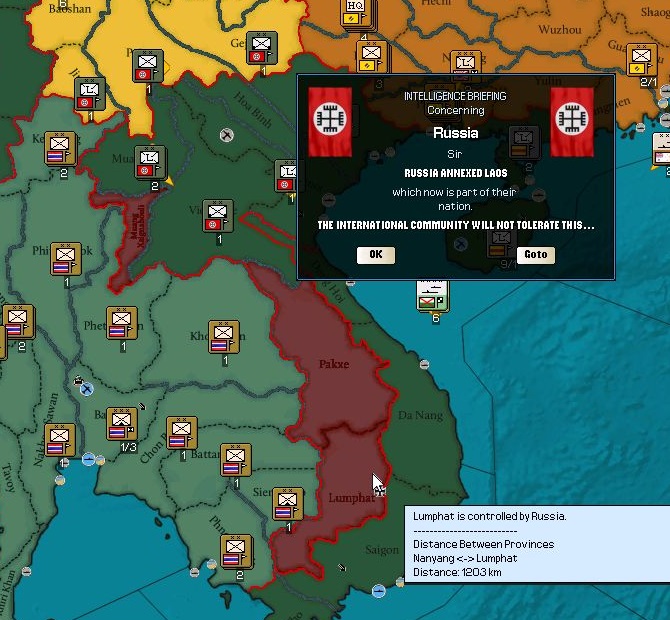

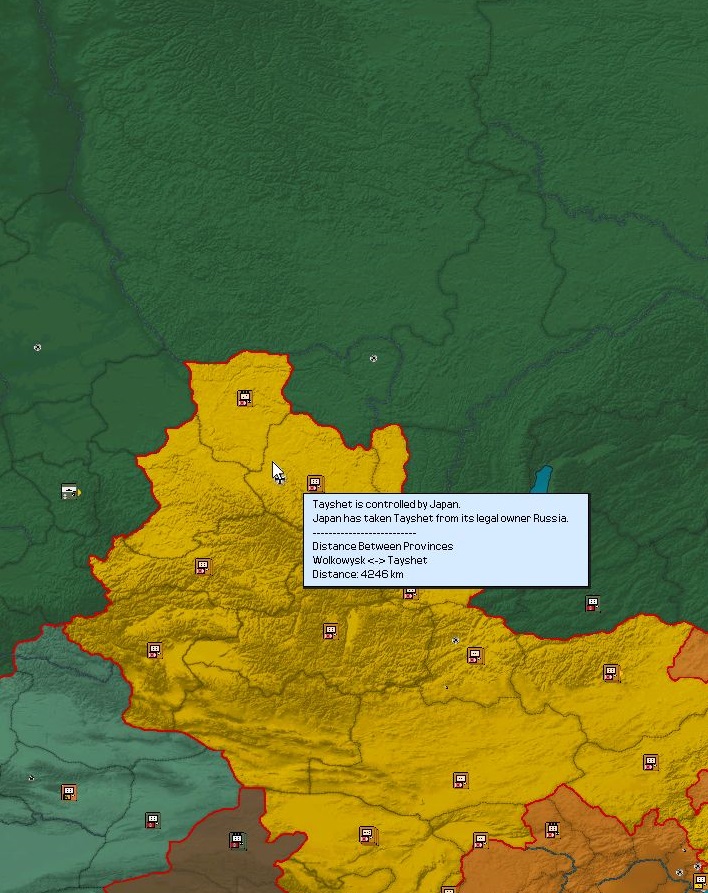

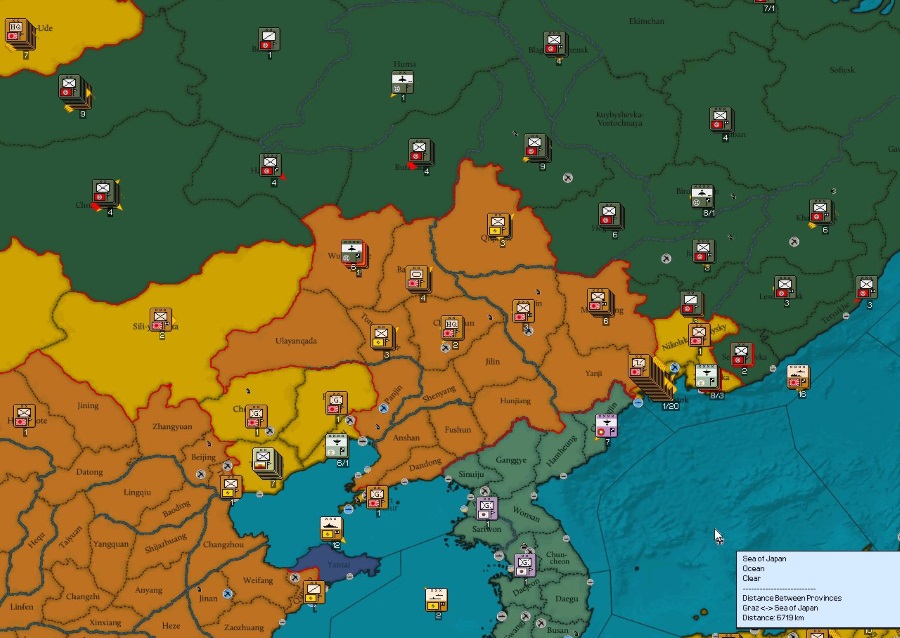

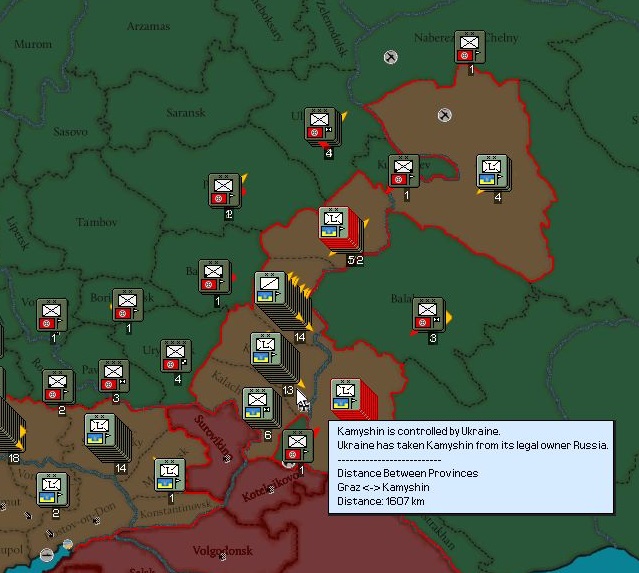

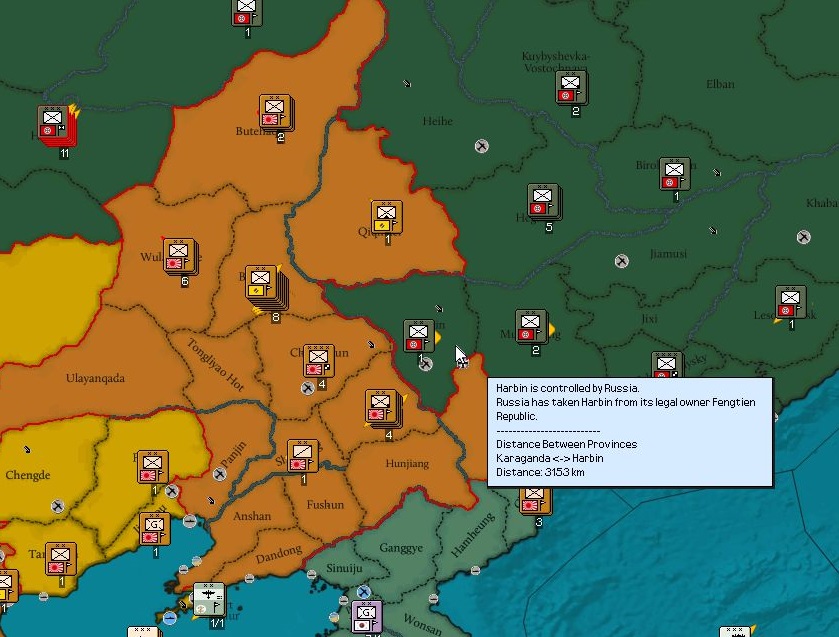

The attack on Turkestan did have one major consequence, in that it informed the Russians that their offer of a grand bargain was not going to be accepted, and so they retaliated by declaring more puppet states in the territory claimed by the Republic of China.

The advance Australasian light armor entered Baku without resistance, cutting off the only rail link between the French forces in the East and their homeland.

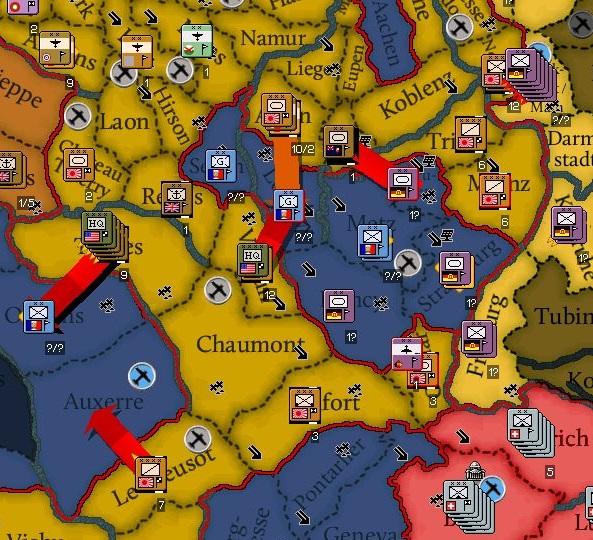

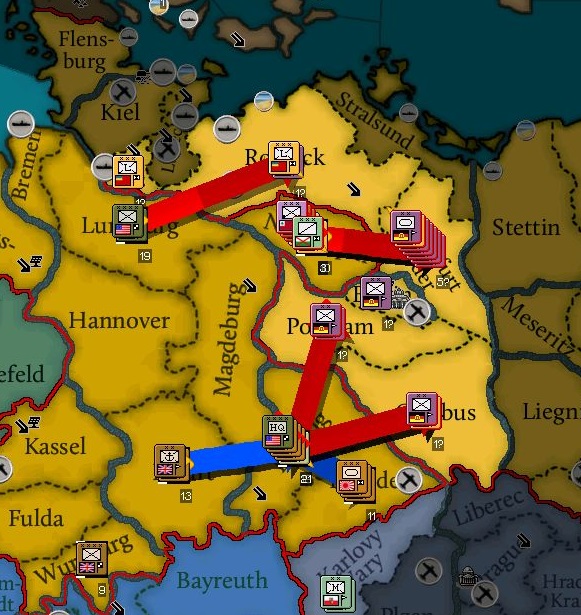

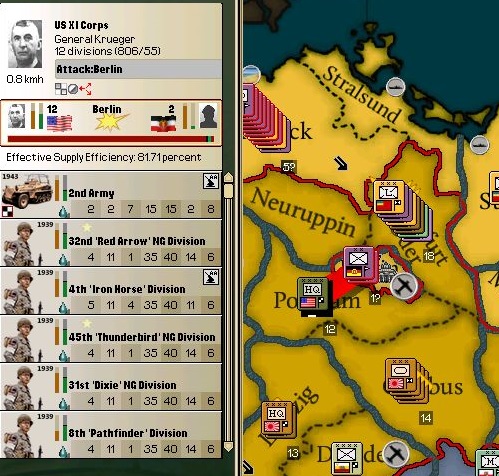

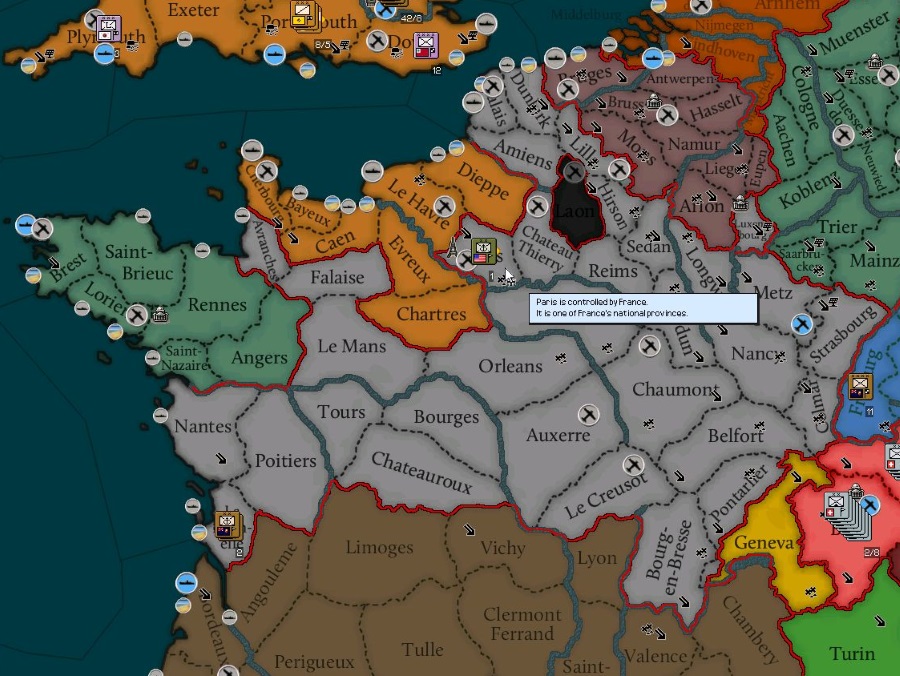

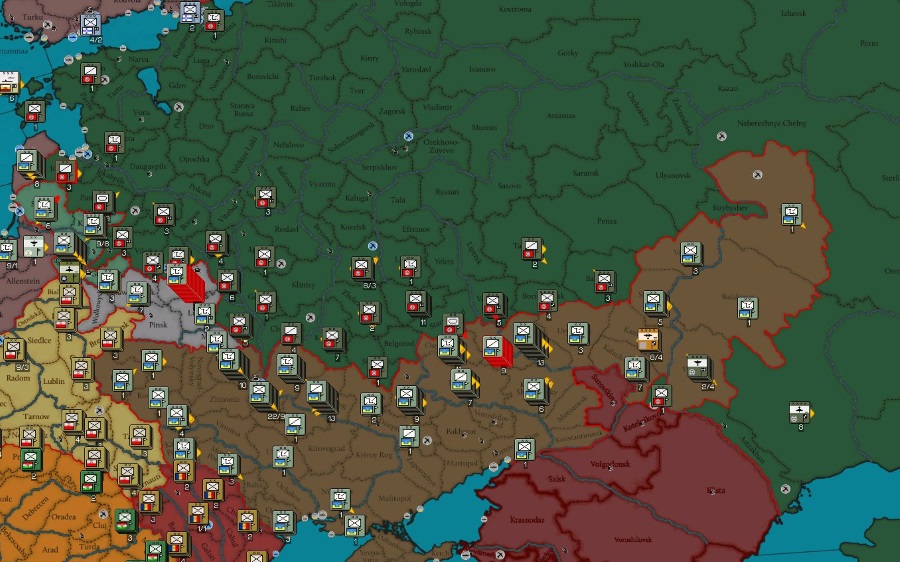

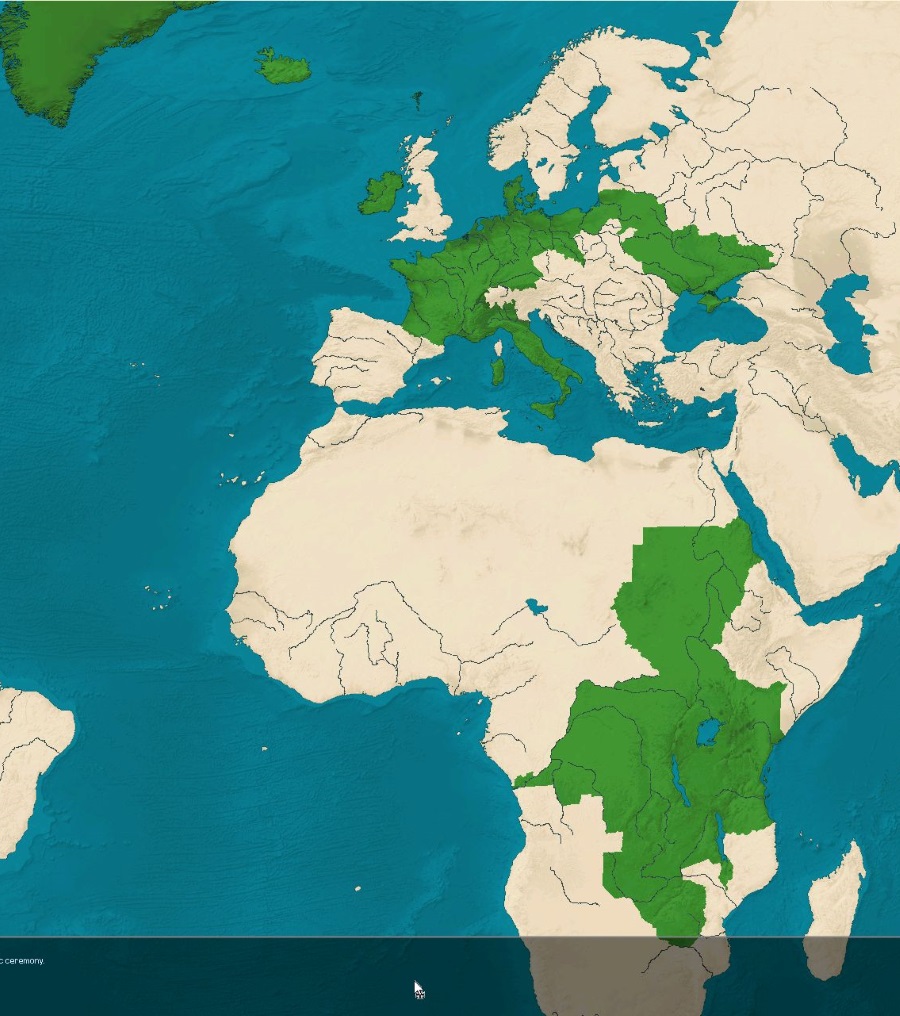

The very next morning, Operation Shogun begun. The first sign of invasion were the waves of aircraft which took off from Southeast England.

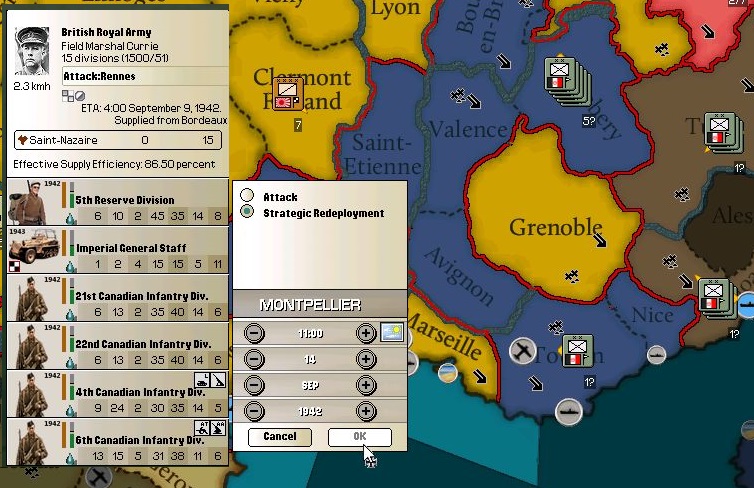

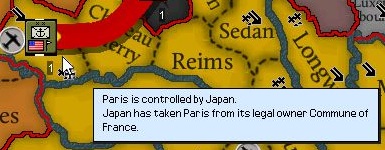

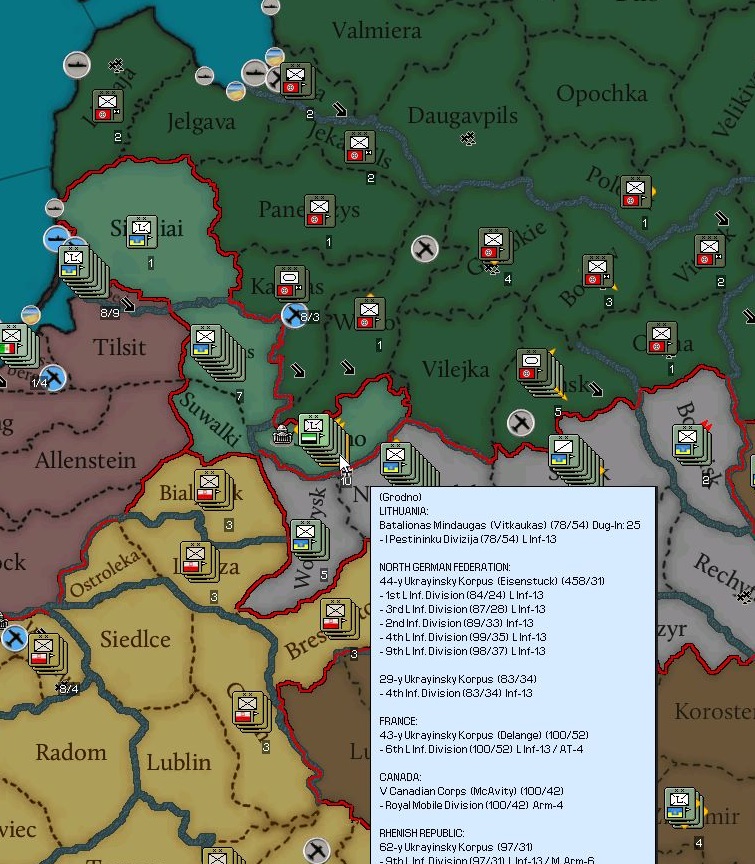

The pilots found that Amsterdam’s garrison had been redeployed to Bruges, and that the city was wide open, and so the American transports which had delivered the new Japanese armor to England were given an escort and told to crash the harbor. Amsterdam was a massive harbor, and the urban center of the Netherlands. If it could be captured without a fight, it would get the invasion off to a good start. The other two attacks on Dieppe and Bruges launched as planned.

The Bruges landing commenced an hour before the Dieppe landing. British and Canadian marines, backed up by Japanese armored divisions, attacked the Dutch defenders. The Dutch had never had a formidable army, but the veteran infantry they did had had been lost in America, and so poorly trained recruits were up against experienced marines.

Japanese and British marines attacking Dieppe found just a single French garrison division, which had been heavily bombed by Entente aircraft.

The Dieppe garrison had been unable to prevent the beach landings, and then had been surrounded in the city of Dieppe itself. They surrendered within four days of the initial landings.

The Amsterdam landings went off as expected, with two Japanese armor divisions seizing the city virtually unopposed. The Dutch populace, victims of a French-backed Totalist coup, regarded the invading liberals with a sense of relief more than anything else.

The port of Amsterdam allowed more divisions to pour in, and the first divisions that had landed moved inland to seize Arnhem.

Dieppe was under British control a few days later and was ready to take in reinforcements.

Bruges, which had been expected to be the easiest landing of all, turned out to take the longest, though it would not take remotely as long as the Cornish landings had.

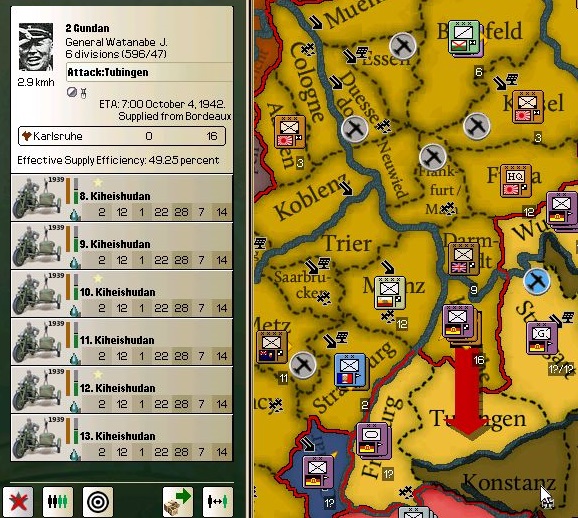

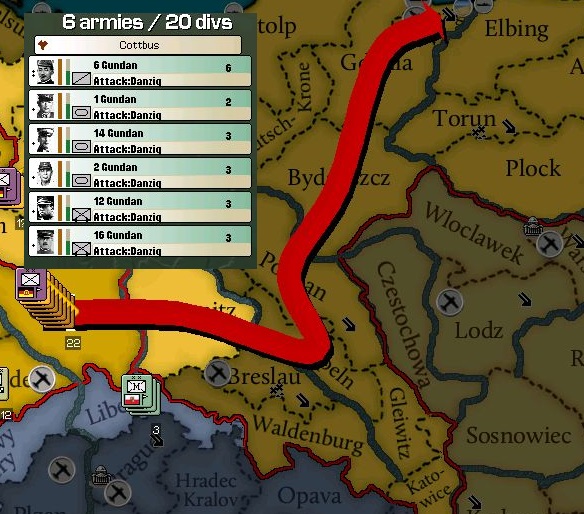

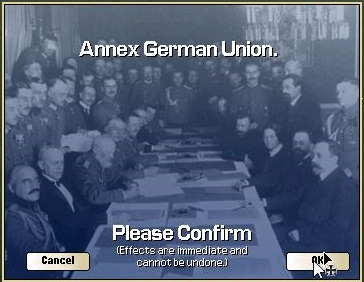

Now that Japanese armor was ashore in great numbers, it was time to see just how effective Sakai’s doctrine of mobility would be. The Entente had successfully cut off the bulk of the Internationale army from the homeland, and their tanks would be able to travel on the good Western European roads quickly. Armored divisions were dispatched from the Netherlands proper to take the Bruges defenders from the rear. Optimistic assessments of coastal defenses had turned out to be accurate, and now the Entente aimed to put ashore as many divisions as possible. Operation Shogun was a success, but the war was not won just yet. The major French cities needed to fall in order to cripple the Internationale war effort, and the Entente had to try and capture as much territory as possible before winter, or opportunists, came.

Entente planners knew that they would not be able to hide the preparations for the assault on Europe forever, but their luck had held through April. French strategic thought had been focused on the pursuit of a massive offensive into the Middle East, to gain oil lost after the recapture of Texas and to try and deny resources to the ever growing Entente industrial base that was bound to outproduce the Internationale in the long run. The arrival of over a hundred Entente divisions forced a stalemate instead. The French knew that a massive force was in their path, but what were not so sure about what national armies were most prevalent in the Eastern Command.

This began to change when the French made their first attempt at breaking the lines in Iraq. The experienced French commanders and veteran troops believed they had a good chance of breaking through the enemy line.

Their expertise was thwarted by the sheer scale of the defensive fortifications around Karbala that had been built in the weeks since the two armies had settled into the stalemate.

The French called off their first attack on Karbala after just a few days, having taken nearly thirty thousand casualties, including losing sixty-one tanks. What they also found was that there were hardly any Japanese or North American divisions. The French command had assumed that, based on underestimates of the size of the new Asian Entente armies, North American divisions were the ones shoring up the lines in the Middle East.

The realization that the Japanese and North American armies were not in the Middle East caused the neutral powers of the world to recognize that something was afoot. The Vozhd in particular was keen enough to see what was about to happen, and he decided that he wanted a piece of the action.

A Russian proposal for a grand bargain that would return Western Europe to the Entente while Russia would seize Eastern Europe. The Minseito absolutely refused to consider it, but also did not wish to publicly provoke Russia at that point in time, so the proposal was ignored and would remain classified until 1985.

As spring rolled into summer, the ideal invasion dates for the longest possible summer campaign came and went, as the Entente logistics network was overworked.

Finally, the Entente decided that a date needed to be set, and they decided that the invasion would launch immediately after the newest Japanese armored and motorized divisions arrived from the Home Islands, in late July. It was not optimal timing, but it would have to do.

While the passage of the optimal dates led some in the Internationale to be optimistic and believe they had until 1943 to prepare for an invasion, most commanders were not fooled and resorted to novel strategies to try and put the Entente off balance for as long as possible.

The Italian raid of Alexandria served as a distraction that pulled away Indian cavalry divisions earmarked for the invasion of Persia, but the Italians did not have the naval power to support a large invasion force.

More effective for the Internationale was the continued support of the Algerian rebels who declared victory in their war of liberation after seizing Tunis. The Entente continued to shun National France especially now that they held naval bases in Egypt.

About a week before the Japanese armor was scheduled to arrive in England, the Persian Gambit was given the go ahead. The main force meant to drive to the Caucasus was about half the size as originally planned, but the arrival of more French divisions on the line in Syria meant that more of the intended invasion force had to be left where it was to hold the line.

The Entente was cutting it close, as Turkestan was in a state of collapse by July.

In the end, their timing turned out to be very good, as the power of Turkestan to resist was shattered, but the Russians were not too close that they would cross the Persian border before the Entente could secure it.

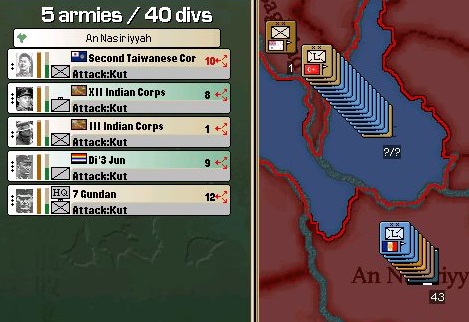

A force of Burmese, Taiwanese and Indian infantry moved to do just that, while a mobile force of Chinese, New English, Indian, Japanese and Australasian divisions struck the main blow.

Most divisions pushed northwest towards Baku, while the Chinese divisions peeled off to secure Teheran.

The only resistance the Turkestan could put up to protect their vassal was one battered infantry division pushed south by the Russians.

The Australasian armor pushed ahead of every other division in order to scout, and found that Azerbaijan and Armenia were virtually undefended. Every French division in the region had been sent to try and break the line in Iraq and Syria.

The Entente conquest of Persia would cost virtually no blood or treasure.

The maneuver caught the Internationale by surprise, and their attempts to break the stalemate became more aggressive. They suffered more than fifty thousand casualties in a second attempt to take Karbala.

The attack on Turkestan did have one major consequence, in that it informed the Russians that their offer of a grand bargain was not going to be accepted, and so they retaliated by declaring more puppet states in the territory claimed by the Republic of China.

The advance Australasian light armor entered Baku without resistance, cutting off the only rail link between the French forces in the East and their homeland.

The very next morning, Operation Shogun begun. The first sign of invasion were the waves of aircraft which took off from Southeast England.

The pilots found that Amsterdam’s garrison had been redeployed to Bruges, and that the city was wide open, and so the American transports which had delivered the new Japanese armor to England were given an escort and told to crash the harbor. Amsterdam was a massive harbor, and the urban center of the Netherlands. If it could be captured without a fight, it would get the invasion off to a good start. The other two attacks on Dieppe and Bruges launched as planned.

The Bruges landing commenced an hour before the Dieppe landing. British and Canadian marines, backed up by Japanese armored divisions, attacked the Dutch defenders. The Dutch had never had a formidable army, but the veteran infantry they did had had been lost in America, and so poorly trained recruits were up against experienced marines.

Japanese and British marines attacking Dieppe found just a single French garrison division, which had been heavily bombed by Entente aircraft.

The Dieppe garrison had been unable to prevent the beach landings, and then had been surrounded in the city of Dieppe itself. They surrendered within four days of the initial landings.

The Amsterdam landings went off as expected, with two Japanese armor divisions seizing the city virtually unopposed. The Dutch populace, victims of a French-backed Totalist coup, regarded the invading liberals with a sense of relief more than anything else.

The port of Amsterdam allowed more divisions to pour in, and the first divisions that had landed moved inland to seize Arnhem.

Dieppe was under British control a few days later and was ready to take in reinforcements.

Bruges, which had been expected to be the easiest landing of all, turned out to take the longest, though it would not take remotely as long as the Cornish landings had.

Now that Japanese armor was ashore in great numbers, it was time to see just how effective Sakai’s doctrine of mobility would be. The Entente had successfully cut off the bulk of the Internationale army from the homeland, and their tanks would be able to travel on the good Western European roads quickly. Armored divisions were dispatched from the Netherlands proper to take the Bruges defenders from the rear. Optimistic assessments of coastal defenses had turned out to be accurate, and now the Entente aimed to put ashore as many divisions as possible. Operation Shogun was a success, but the war was not won just yet. The major French cities needed to fall in order to cripple the Internationale war effort, and the Entente had to try and capture as much territory as possible before winter, or opportunists, came.